#20 - In Defense of Traditional Architecture

All architecture is traditional. You need to know which tradition you are in.

In This Issue

In Defense of Traditional Architecture

If you are a new reader, you should know that I am a residential real estate developer based in Toronto. I started my career in architecture, but have been working in development for much longer than I ever worked as a designer.

I was recently catching up with a friend, and we were discussing the architecture of recent development applications in Toronto. The conversation turned to 101 Spadina, a project designed by Audax for Devron Developments. My friend told me that some development industry people have been criticizing this project, claiming that it’s overly referential to traditional architecture, or something like that. That it's ersatz classical. Hokey.

When I heard this, it surprised me — not because I haven’t heard that kind of criticism before, but because it felt so disconnected from how I interpret this building.

Everyone I’ve talked to thinks this project is great. It is one of the nicer designs proposed in Toronto over the last few years. It does sit proudly within a tradition that is rooted in classical architecture. But the design team has handled the details very well, and has created a beautiful project that seems fresh while using some traditional principles. Especially the ground floor — just look at it!

When I was getting my architecture degree, I heard arguments against traditional design a lot. Some professors and students were pretty dismissive of it. The most common criticisms went something like this:

It’s “normative” — a fancy word for being based on prescriptive or idealized principles rather than expressive freedom. The idea is that if you’re following someone else’s rules, you’re not being truly creative. Bad.

It’s dishonest — traditional forms obscure the true materials and structure. A masonry building clad in stone might mislead people into thinking it’s made of load-bearing stone. Bad.

It’s outdated or regressive — it reflects values from another time, and doesn’t express the prevailing spirit or mood of today. Some of my more... politically engaged professors even tried to associate it with conservative or fascist politics.

It’s anti-modern — decorative, overly expressive, and unwilling to engage with the idea that form should follow function. Modernism, which is ironically quite old now, tends to favor minimalism and tectonic clarity.

When I was in school, I took these arguments seriously. But after working as a builder, they feel more like rationalizations for aesthetic preferences than robust ideas about what architecture is for.

The Myth Of Originality

One tension struck me early in architecture school. A handful of professors were deeply suspicious of tradition, but totally fine with students inventing their own formal systems. How those systems were generated didn’t really matter. If you created your own rules and followed them rigorously, that was considered good.

So we all wrote our own little design algorithms. Student projects became abstract formal exercises, often disconnected from structure, materials, or detailing. Human judgment mostly kicked in if the generated form got too weird or too boring. The emphasis was on originality and process.

But here’s the funny thing: despite each student’s unique process, the results often looked kind of the same. And this observation has persisted long after architecture school. For example, lots of contemporary buildings are glass boxes.

Sometimes it is one box.

Sometimes it is a bunch of boxes.

Sometimes the boxes are stacked neatly. Sometimes messily.

Sometimes the boxes are wrapped in a striking skin.

This is all fine, of course, because I don’t think architecture needs to be completely original all the time. And boxes have a lot going for them! They’re efficient, easy to decorate, and straightforward to build. In many ways, boxes are the best.

But what’s strange is that many of the firms churning out glass boxes will tell you traditional architecture is unoriginal and constraining. That’s where the argument falls apart for me.

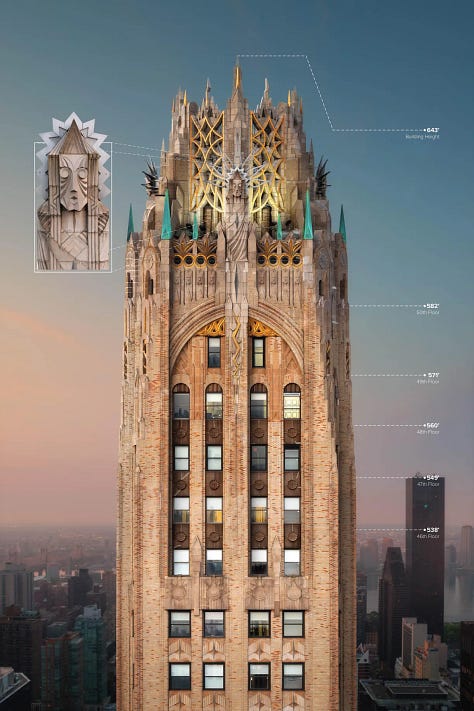

Here’s a selection of skyscrapers photographed by Chris Hytha. If you ask me, these buildings exhibit as much or even more variety and originality than the collection of glass boxes — even though they all follow traditional design principles to varying degrees.

I often wonder why we are so quick to dismiss traditional forms as unoriginal, only to build the same glass boxes over and over.

All Architecture Is Traditional

Pretty much all architecture belongs to a tradition — whether we admit it or not.

If you design glass boxes, you’re actually in the Glass Box Tradition, which is nested within the Modernist Tradition. That tradition includes the Farnsworth House, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a giant of architectural modernism. He championed simplicity and structural honesty.

At least, that’s what he said.

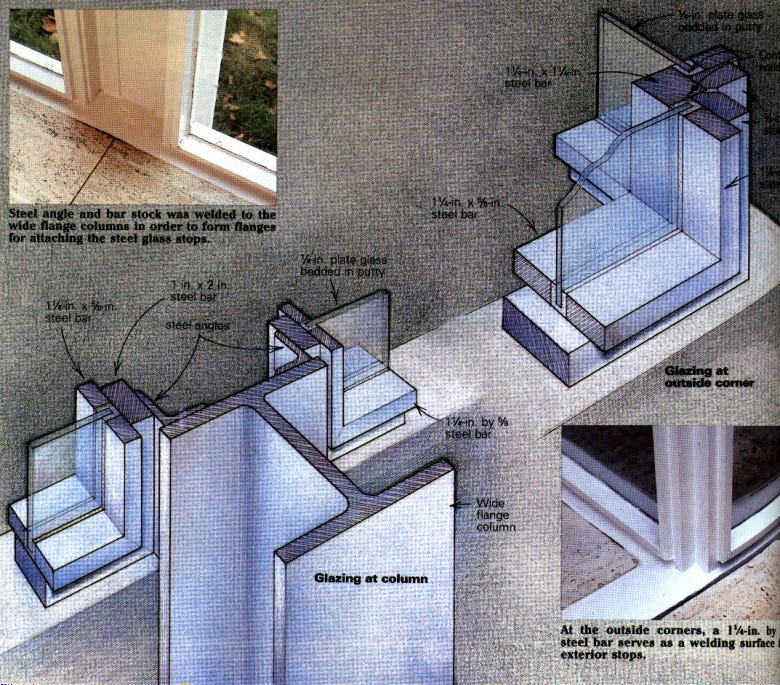

But if you look at his buildings, they’re anything but simple in their detailing, or honest in their structural expression. For example, any builder will tell you the minimalist window detail below is borderline insane. It’s much harder to build than a conventional window sill, offers less tolerance for error, uses more expensive materials, and has zero insulation value.

(Mies and the Farnsworths had a big dispute about budget overruns, for what it’s worth…)

Let’s look at another Mies project: the Seagram Building. A wonderful building — one of my favorites. It has a steel structure, and Mies wanted that structure to be visible. But building code and common sense required the steel to be encased in fireproofing and shielded from the elements, so he added decorative steel I-beams on the exterior to be suggestive of the hidden internal frame.

Is this more honest than a brick wall enclosing a wood-framed structure?

I am not so sure.

But the principles that govern Miesian modernism continue to influence how buildings are designed and constructed today.

Normative Is Good, Actually

Let’s recap:

Originality, as we’ve seen, is mostly a myth. And there’s no escaping tradition per se. Even when we think we are being creative, we are often working within a design language that we didn’t create ourselves.

That makes sense, because all creative work is constrained — by time, money, materials, and experience. Architects operate within this condition of scarcity. They don’t make a ton of money, as we’ve discussed before, so they’re limited in how many new problems they can solve in a given project. If you have to worry about everything, you may not have time to care deeply about anything.

So it’s no surprise that architects often reuse the same design elements across projects to save time. In design software, these ready-made elements (such as a door, a window, or a toilet) are called blocks or components.

I like to think of traditional architecture in the same way: as tools instead of rules. As a massive catalog or library of components you can use freely. Viewed this way, tradition is liberating rather than oppressive. It offers time-tested solutions to specific problems — proportions, spans, construction tolerances, weather protection — that you don’t have to reinvent every time.

Using these tools means you can set aside more time and energy for the parts of your project that you really care about.

For example, even if you’re not building in brick, it makes sense to design façade elements around standard brick dimensions — it helps standard windows, vents, and other components fit cleanly. It naturally produces patterns and proportions that feel familiar and pleasing. Besides, are you really going to reinvent a whole new set of standard dimensions for every project and expect the construction supply chain to bend around you?

Beyond practical constraints, there’s an aesthetic cost to rejecting tradition wholesale: you have to invent a new visual language from scratch. That’s hard to do! Civilizations will take centuries to come up with just one really good style, and some never even get that far. And you’re going to generate one all by yourself? If you spend your time developing a new theory of beauty, something else is going to suffer — probably the details of your designs.

Brian Hagood, an architect in Toronto, has coined a term I really like: the architectural striptease — when modern buildings are stripped of detail and beauty.

My take: if you ignore tradition entirely, you’re more likely to flail. Have you decided you hate symmetry? You can spend weeks nudging windows back and forth on a computer screen — searching for the perfect random arrangement — instead of just designing a really nice window that your client’s neighbors will compliment.

Tradition isn’t a limitation. It’s leverage. It’s a vast and generous toolkit — one that lets you focus your limited time and resources on what really matters. Creativity doesn’t come from rejecting tradition — it comes from choosing how and when to use it well.

In The News

There’s a lot to talk about this month. The most exciting thing is that Canada has a federal election scheduled for April 28th, and housing is a central issue.

For the first time, both the federal Liberals and Conservatives are putting serious reforms on the table. It actually feels like a competition for who can propose the most meaningful changes. The usual political instinct is to propose the smallest reform that earns credit without changing much. This is a real sea change.

Pierre Poilievre has done a good job diagnosing the problem — especially around planning delays, overregulation, and misguided demand-side incentives. Until recently, his policy proposals were vague but mostly pointed in the right direction. That changed with a recent pledge to remove the 5% GST on new homes priced below $1.3 million.

Then Mark Carney raised the stakes. His plan also scraps the GST, but only for new homes under $1 million and only for first-time buyers. He also pledged to cut municipal development charges in half, and to make municipalities whole for doing so. On top of that, he committed to starting a public builder of affordable housing and reintroducing the MURB program, a 1960s–70s-era tax deferral scheme that allowed investors to use real estate losses and depreciation to offset unrelated income. This is a very big deal.

Both parties still have much room for improvement. The Conservatives need to do more about stabilizing and expanding CMHC programs, and creating better incentives for capital investment. This is low hanging fruit that feels ideologically aligned, and is especially urgent in light of Carney’s announcement. The Liberals still lean on familiar ideas with mixed track records — like paying municipalities to process applications faster or launching a public builder. These are both high-effort, high-complexity strategies with poor recent results.

But even with these shortcomings, things are moving in the right direction. Political leaders are finally proposing reforms that could actually move the needle. I’m optimistic this will continue through the election and beyond.

That’s a wrap.

I write this newsletter because I like to connect with smart people who are doing interesting things. Feel free to reach out with questions or suggestions by replying to this email.

Thank you for reading, and have a great April.