In This Issue

Are You Paying Your Architect Enough?

Before getting into real estate, I studied and worked in architecture. I didn’t last very long in that profession — just two years or so. Since then, I’ve worked as a developer with many talented architects on a range of project sizes and types. That’s why an X post from Toon Dreessen caught my eye a couple of weeks ago, and I fired off a quick reply of my own.

One of the big differences I noticed after moving to Toronto is how much less architects here earn for their work. When I have asked Canadian Architects outside of Ontario, they have told me that their fees tend to be higher. Now, I haven’t done a big national survey of architects, but my experience so far suggests that for some obscure reason Toronto architects earn significantly less than their counterparts in other provinces and in the US. You might think that a developer would be happy about a local market where consultant fees are low. Everyone likes to pay less, right?

Now that I’ve spent a few years working on projects in the GTA, I have come to think this is probably a bad thing. The most obvious reason is that if you give someone more resources then you can reasonably demand better service from them. There’s a limit to this, of course. As service gets better, there will be diminishing returns to throwing more money at an architect. The whole thing gets a bit complicated so let me set the stage by sharing an experience that I had some years ago…

My company had been giving business to a certain firm (let’s call the owner Architect Andy) for many years, but their performance had been slipping. They were making numerous coordination errors that led to delays and unanticipated costs during construction. They also had a corporate culture that made them somewhat difficult to work with, and they were slow to accept responsibility for mistakes. People at my company complained about them a lot, but we knew what to expect from them and they were pretty cheap. Definitely not bottom of the barrel, but if you told them what you wanted their fee to be, that’s more or less where it would come in. And so we continued to use them for new deals.

One time we were working on a new project, and my job was to lead the project team through the design and entitlement process. This project was complex and we needed to hit a very aggressive schedule for both design and construction. Given the difficulties that we had been having with Architect Andy, I wanted to try out another firm — let’s call that owner Architect Bridget.

Architect Bridget had done only limited work for us before, but our experience with them was fantastic. They were not only pleasant to work with, but they produced higher quality work on shorter timelines. Architect Andy, on the other hand, missed more deadlines than they met. To make matters worse, Architect Andy had already told us that they wouldn’t be able to meet our aggressive project schedule, and they would need a few additional months to complete their work. I was confident that if they asked for a few extra months up front, then the actual delay was likely to be even longer. Architect Bridget had provided a dedicated team for our previous project, whereas Architect Andy had the same two or three staff working on several of our deals. Naturally, whenever they missed deadlines, they complained about being too busy on our other projects.

From the perspective of quality and speed, Architect Bridget seemed like the obvious winner. There was only one problem… Architect Bridget was expensive. They charged around double the fees that Architect Andy was asking for.

To make a fully informed decision, I needed to look deeper — beyond just the fees and design schedule. I needed to understand the total financial impact of this decision, so I calculated our carrying costs for the project during construction — things like the contractor’s project operating costs (“Division 1” in construction parlance), insurance, and interest expense. I concluded that even with Architect Bridget’s higher fees, we would probably break even just by avoiding design and permitting delays (they were willing to commit to a faster design schedule). More difficult to calculate, but just as real, was the very high likelihood that Architect Bridget would make fewer errors that would require costly field revisions during construction. At the end of this analysis I was convinced that we should change architects, so I called a meeting of stakeholders and made my pitch. I said that we should switch architects, which would cost more upfront, but would (with reasonably high confidence) save us a lot of money over the course of the project.

There were two camps in this meeting. One wanted to proceed with Architect Andy, and the other with Architect Bridget. Reasonable arguments were made in both directions.

Team Andy wanted to save on the architectural fees, because those were concrete and measurable. The future savings from using Architect Bridget was unknown and uncertain. They figured we could simply manage Architect Andy more aggressively to get better performance. Team Andy was also inclined to refuse any proposal where the fees were “above market”, even though they agreed that Architect Bridget was likely to outperform Architect Andy. To put it another way, they were willing to run the risk of delays and change orders because they didn’t like the idea of paying our architects more than the prevailing fee level for our local market.

Team Bridget didn’t really care what the market was paying — they just wanted the best overall financial outcome for the project. If the fees were higher, so be it. In fact, Team Bridget’s argument was that we should spend more money upfront, in exchange for a team with a track record of better performance, with a higher quality of service. This higher quality made it probable (but not guaranteed) that we would save time and money, even after paying the higher fees. This is because the anticipated cost of delay was so high that even a few months of time saved would more than make up for the difference in fee. This uncertainty made Team Andy uncomfortable — what if Architect Bridget didn’t end up performing? Then we would have higher fees and all of the costs of delay!

So… who do you think we ended up using?

I’m not going to tell you who we ended up using, because it’s not all that important. But these are the types of tradeoffs that a developer faces every day. There is lots of uncertainty, and an architect that was great last year might underperform this year.

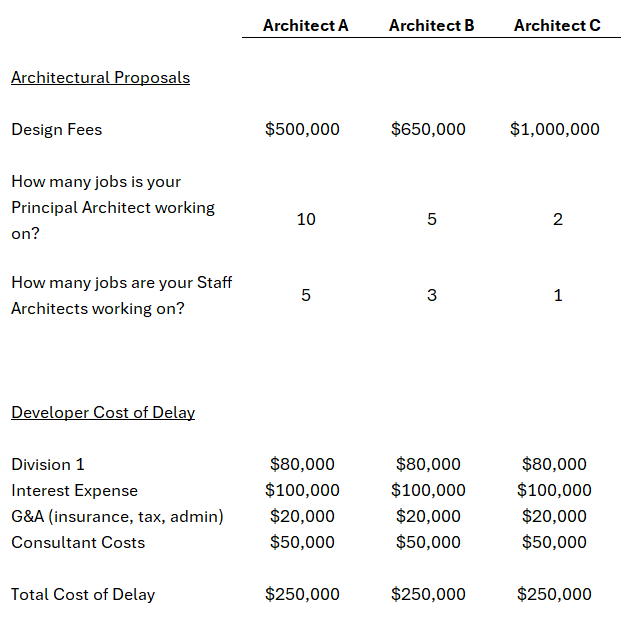

If you are a developer, l recommend doing the following exercise when comparing bids for architectural services: calculate the (quantifiable) costs of monthly construction delay at around 50% of construction completion. Add up your Division 1’s, contractor fees, insurance, and interest expense. Also add in any miscellaneous costs that run on a monthly or hourly basis for the duration of construction, like designer/engineer inspections, project monitoring, and consultant visits during the Construction Administration phase. Let’s assume for the sake of example that that number is $250,000 for your project. This is your cost of delay.

Now look at your architectural bids. Here’s a simplified sample I made up.

If the price difference between the fee proposals is equivalent to only a couple months of delay, then you might want to consider them to be essentially the same. Then prioritize level of service much more than price when comparing them.

Sit down with the principal architect and ask them a bunch of questions:

Will each person be dedicated solely to your project? If not, how many other projects will they be working on?

What is their philosophy around scope boundaries and requesting additional fees?

Will they commit to a reasonable amount of time for closing RFI’s and submittals?

Are they responsible for coordinating drawings across all consultant disciplines?

Will they be responsible for managing meetings, recording and circulating minutes, and following up on action items?

Next, call 4-5 client references for current projects they are working on. Ask about the specific people that are proposed for your project.:

Are they responsive?

Do they hit deadlines?

How good are their drawings? Are there many errors?

Do the other consultants and the construction managers like working with them?

Do they take responsibility for mistakes?

What you’re trying to uncover is the likelihood of delays and errors. If your project architect is a passive participant rather than a project manager, or if they are working on half a dozen other projects, then their drawings are probably not going to be very good. But if they are accountable for the entire consultant team and are working on your project only, then the drawings are probably going to be much better.

In the example above, consider that hiring Architect A versus Architect C will save you $500,000 in fees. That’s a lot of money, so you might be tempted to take the cheaper option. But then you consider how stretched their staff are, and the relative probability of them causing delays or budget overruns because of drawing mistakes. If they cause 2 months of delay or $500,000 in overruns (or wasted time), then the more expensive architect will have saved you money.

Bottom line: As in all areas of life, you generally get what you pay for. And a good, well-resourced architect will supercharge your project. A bad one can cost you millions — and yes, I mean millions — of dollars. There will also be coordination issues that may not cost you directly during construction, but which will probably reduce the quality, ease of operations, and public perception of your building.

Not investing wisely in this part of your project team is one of the most common and tragic mistakes I see in development.

In The News

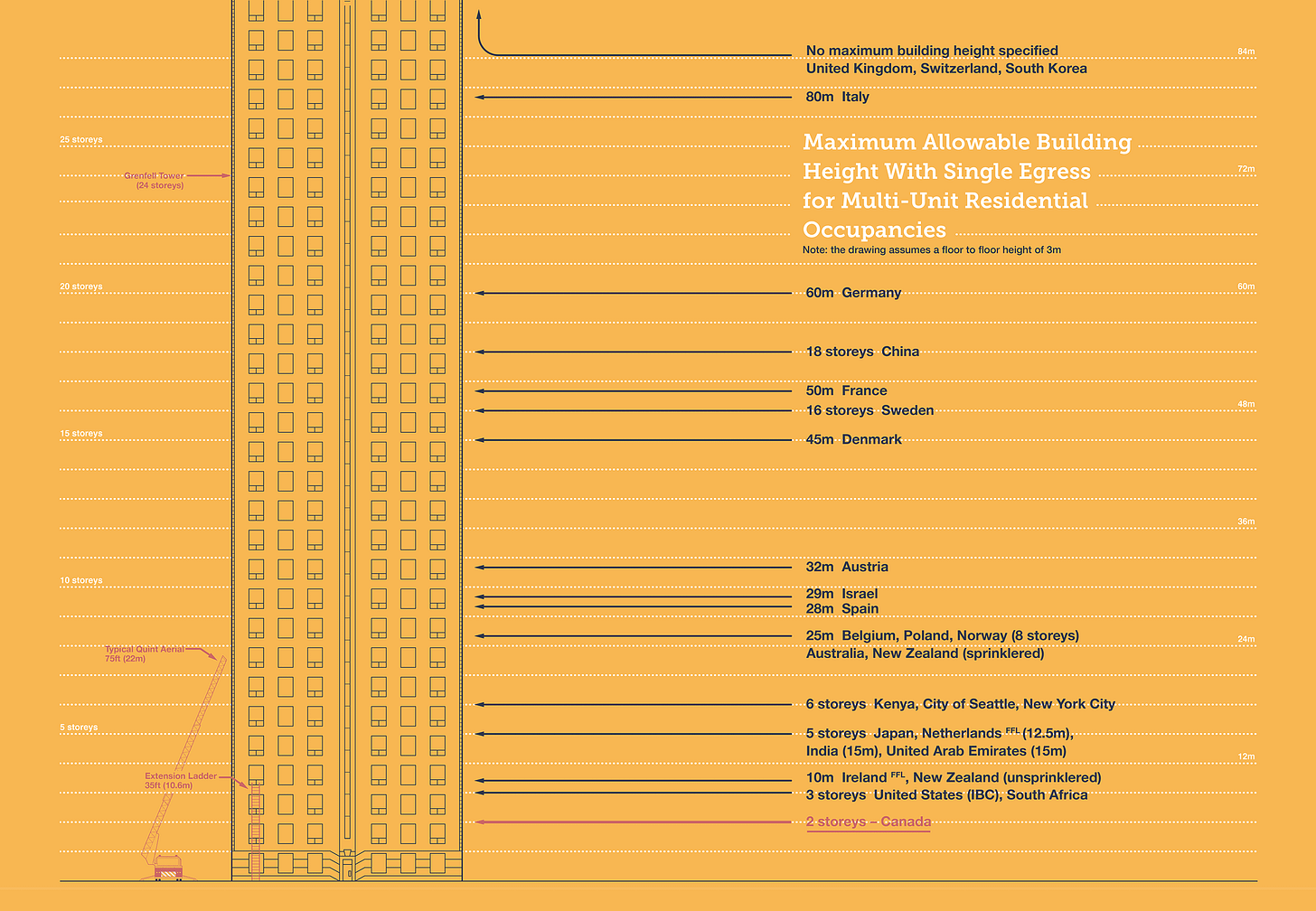

In August, British Columbia’s provincial Housing Minister, Ravi Kahlon, announced that his government was revising the provincial building code to allow single-stair residential buildings up to six stories.

This is a big deal. Very much to our own misfortune, the US and Canada are two of the most restrictive countries in the world when it comes to the height of buildings which are allowed to have only a single egress stair. Conrad Speckert wrote a great piece about this for Urban Progress, which included this terrific graphic.

If you’re interested in learning why this is important, please read Conrad’s article. I’ll just say that there are several really good reasons to allow single-stair egress in apartment buildings. The most important reason is that many small parcels are not viable apartment sites because they are too narrow or shallow to efficiently include two full-sized stairs. Most small multiplex projects have truly ridiculous egress paths because of the two-stair rules. This change will unlock a lot of smaller sites for development.

Additionally, single-stair egress will generally be slightly more space efficient because you need less corridor to serve a given number of units; it allows more of your units to have “dual aspect”, meaning there can be windows facing more than one direction, which is great for natural ventilation; when paired with building code requirements around windows in bedrooms, it allows more flexible designs for larger (3 bedroom+) units. In short, it creates more flexibility in design, which will hopefully allow architects to create more attractive units.

This won’t change BC’s housing stock overnight, but I am very confident that there will be positive change at the margin when it comes to quality. I’m hoping that this reform energizes provincial officials in Ontario, where this change would also unlock thousands of small parcels for redevelopment.

That’s a wrap.

I have now been writing this newsletter for more than a year. It’s been a pleasure to share what little I know, and to hear from so many of you readers. If you have any comments, questions, or suggestions for this newsletter, I would love to hear them. Feel free to reach out by replying to this email.

Thank you for reading, and have a great September.

One of my mentors describes this as, “Fast nickels beat slow dimes.” It’s the inverse formulation but makes the same point: saving money on hard costs but loosing it on soft costs isn’t even a 50/50 call because the unquantifiable costs of delay (opportunity, risk of market change, emotional momentum) are massive.