#27 - When Land Is Worthless

And why affordable housing is suddenly the highest-and-best use for many sites

In This Issue

When Land Is Worthless

Over the last few weeks, the City of Toronto has made several announcements that include an astonishing fact: 65% of the units under construction are either owned by the city, or built in partnership with it.

On one hand, I am very glad that the city is supporting projects to deliver new housing. This is especially important because many of these units will be below-market rental housing, which is where we have the greatest need. At the same time, this is also a really bad indicator for the health of the housing sector.

It means that the private market has all but collapsed, leaving only projects with lots of government subsidies that can move forward. There are real market headwinds, but a lot of the damage is also self-inflicted. It is simply too slow and expensive to build housing in Toronto, and it’s gotten so bad that government is now in the position of subsidizing a sector that it also taxes heavily.

This is probably not a sustainable way to run things. But for better or worse, it’s the market we have today.

And since most of the projects that are advancing include affordable housing or some other feature that qualifies them for government support, let’s look at the basic math behind why this is necessary.

I’m going to use a simple, imaginary project: a mid-sized rental building, in a typical downtown location, with assumptions that are generous by today’s standards. We’ll start with free land and see if the deal works. Then we’ll ask a more uncomfortable question: at today’s costs and rents, what is the land actually worth to a private builder of rental apartments?

Why Projects Don’t Pencil

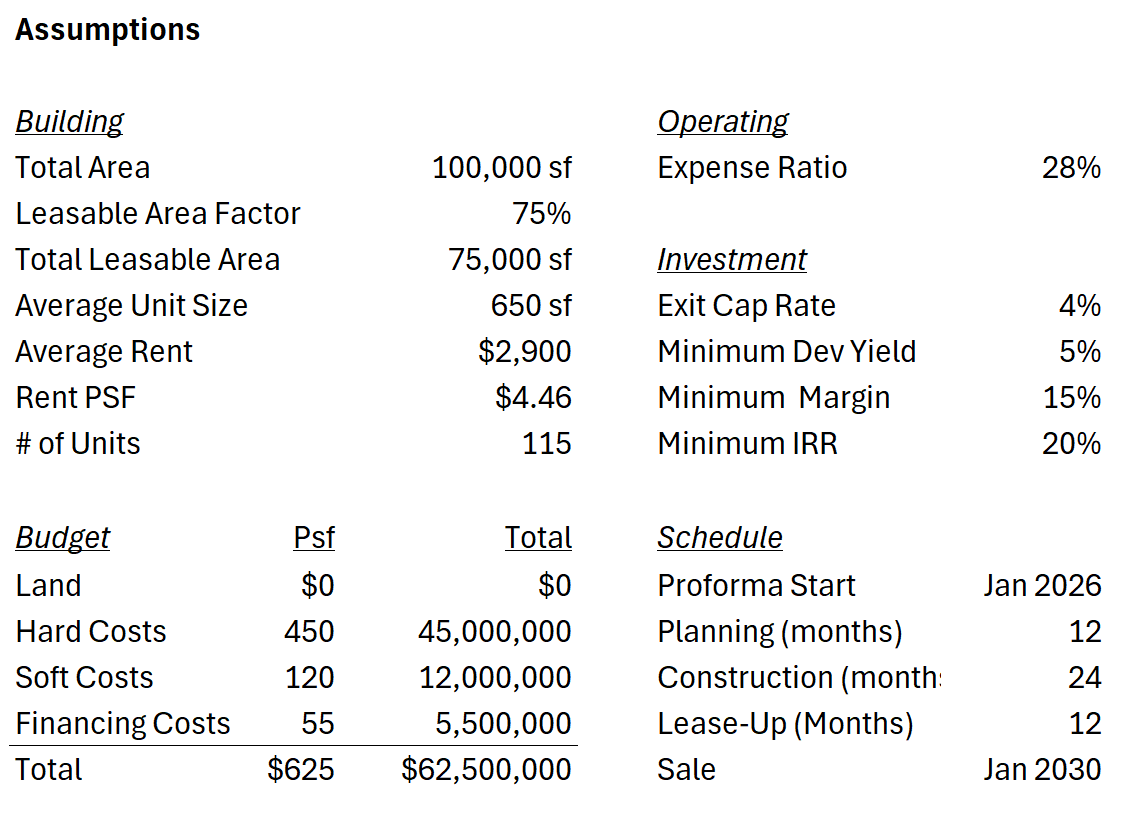

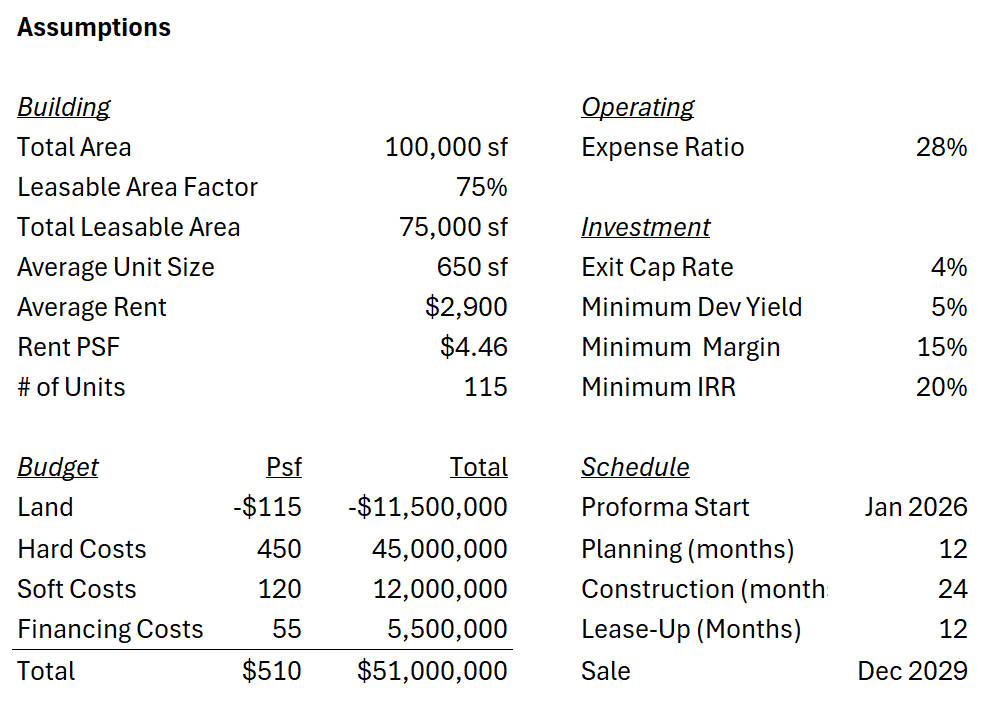

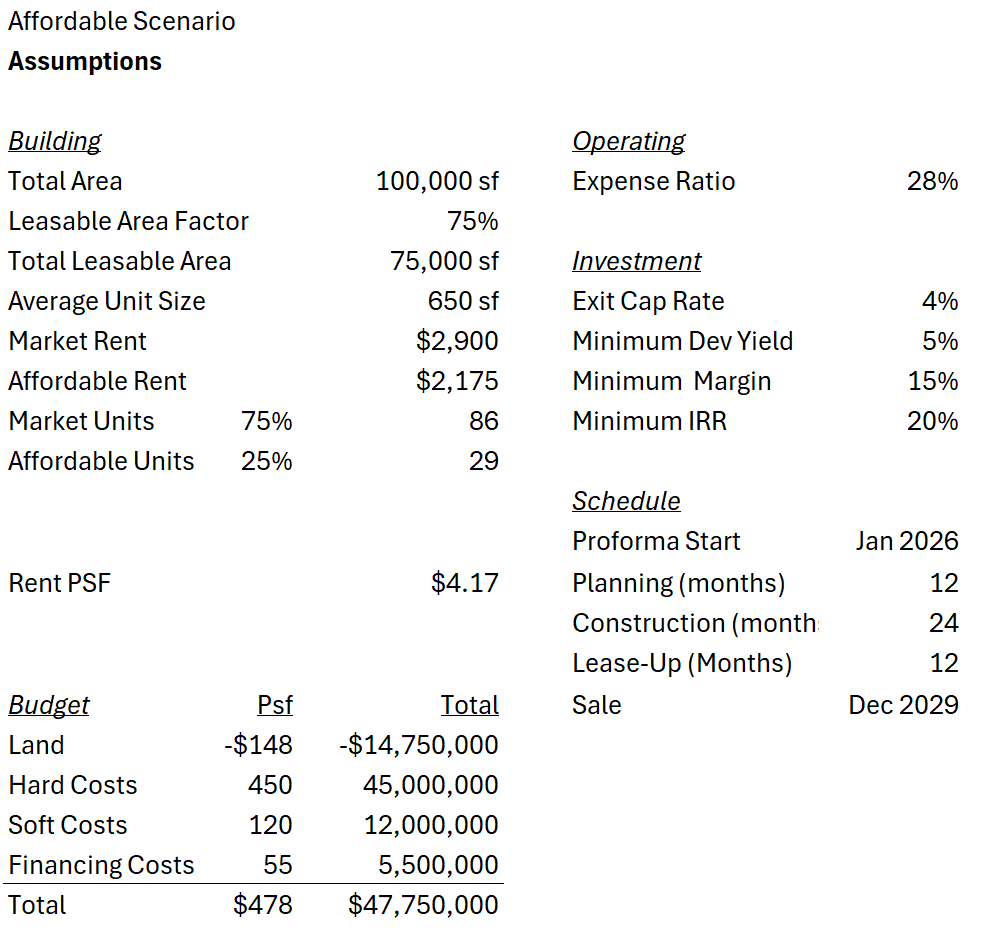

See the table below for my assumptions, which are simplified a bit but roughly reflect current market conditions for a downtown rental site in Toronto.

Once again, note that I have set land value to zero. This is intentional. I want to show you how a rental proforma works, irrespective of land economics. The other section to pay close attention to is the set of minimum financial returns required for project viability:

Development Yield (net income divided by total project cost). We will model net income for this project a bit later.

Margin, which is the difference between the cost of the project and its value at completion. This can be reflected as an absolute dollar value or as a percentage of total cost.

Internal Rate of Return (IRR) which is a rate-of-return calculation that considers the timing of cash flows.

It’s worth noting here that very few deals in Toronto pencil with the assumptions I am showing above. Generally speaking, developers need to be more aggressive along one or more of these metrics to make a project appear viable. At the same time, deals which are aggressively underwritten are struggling to raise equity because they are perceived as overly risky. I am showing you returns that I could confidently raise money for today.

Using these assumptions, we can see how the project performs:

On the left, you see the untrended returns. That simply means I’ve used today’s rents and expenses and held them flat over the life of the project — no inflation, no growth. In the real world, rents and operating costs usually rise over time, especially in core urban markets, which is why the table on the right shows a trended case with 2% annual growth. I like to start with the untrended view because it lets you compare very different deals on the same footing, and it also forces some amount of underwriting discipline. You can make almost any project look good if you assume enough rent growth. Untrended numbers tell you what the deal is worth today, without relying on market forces to save a weak proforma in the future.

What you’ll notice above is that at today’s costs and today’s rents, this deal doesn’t meet our criterion for minimum yield (4.61% versus 5%), but it does meet our minimum margin of 15%.

Now, if you look at the table on the right hand side, you will see that I have escalated rents and expenses at 2% per year so you can see the impact this has on returns. Introducing time also allows us to calculate IRR, which comes in at a meager 10.63%, far below our minimum.

Bottom line: even with free land, this site doesn’t meet a 5% yield or a 20% IRR. At today’s costs and rents, the value of the land for new rental development is below zero. Now, that doesn’t mean the market price is zero; it’s often the case that some other use (or even whatever is currently on the site) is its highest-and-best use under current market and regulatory conditions.

How Subsidies Work

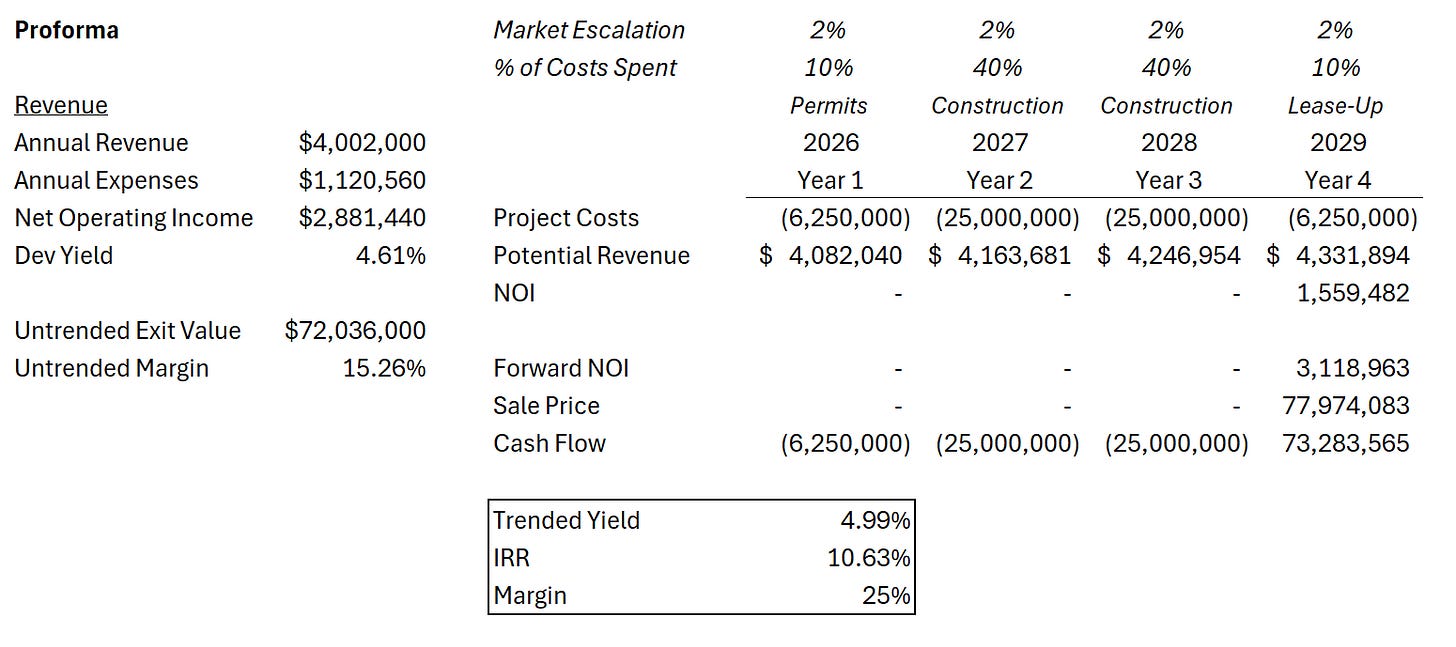

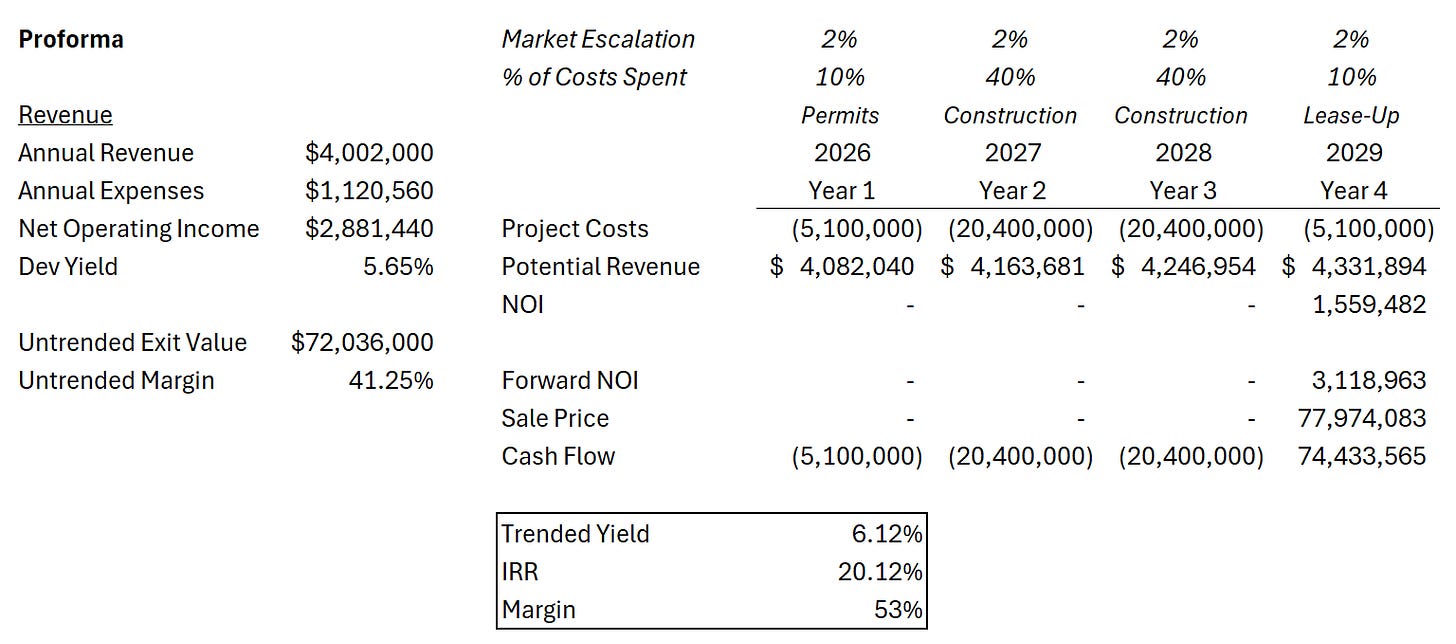

So we know that even with free land, this site doesn’t pencil. So presumably if we did pay something for the land, our proforma would look even worse. But what if the land had a negative value? If you think about it, a negative land value is like a landowner paying us to develop their land, rather than the other way around.

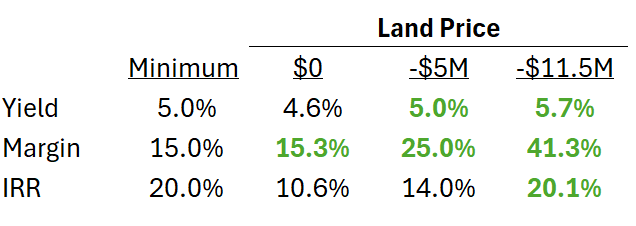

In the table below I have adjusted the land value to solve for a deal that meets all three of our investment criteria.

And here’s a table showing the land value at which each criterion is achieved:

To hit our return thresholds, the landowner has to pay us $11.5 million to take the site off their hands. Obviously, most landowners will not be interested in this deal.

There is an exception, though! There is one player in the real estate market that is very interested in this kind of deal today: government.

There are numerous government programs that subsidize housing construction in Canada. Programs range from mortgage insurance for market rental construction to cash equity for deeply affordable housing.

How Much Does Affordable Housing Cost?

Recall that there are thousands of units currently under development in Toronto that have received government subsidies intended to overcome this feasibility problem.

Except for some federal lending programs, most governments are not in the business of subsidizing market rate apartment construction — they generally want something in return for their subsidies. That something is usually affordable housing — units which are offered to the public or to specific groups at below-market prices. Let’s examine what this kind of requirement does to our land value/required subsidy.

First, let’s assume that we will set rents for 20% of the units at a 25% discount. So if a market unit rents for $2,900, an affordable unit will rent for $2,175. Here’s our revised proforma:

Note that the required subsidy has grown by an additional $3,250,000 (or $28,260 per unit) to provide this level of affordable housing compared to our market rent scenario. To put it another way, we need a subsidy sufficient to reduce our total project cost to $478 psf, compared with the $625 psf that is common in Toronto today. We will come back to this idea shortly.

Now, some people will hear this and say that it’s the need for a financial return per se which creates the problem. If only developers didn’t need to make a profit, then we could deliver more affordable housing!

That sounds intuitive, but it’s backwards. Projects already carry contingencies for cost overruns and inevitable changes. That contingency is part of the cost of the building. The “profit margin” sits on top of all of that. It’s like a buffer for everything else that might go worse than expected, including macro risks. Rents could come in lower, interest rates could spike, construction delays could burn through the contingency...

No lender, including government lenders, will advance funds into a project with zero buffer. If there’s no margin, any surprise could turn into a loss, and the odds of default go way up. Government builders face the same tradeoffs: if they load a project up with affordable housing and other enhancements, they still need enough margin to absorb surprises. In practice, that means their costs will often be higher than a comparable market building.

At the level of development/operating entity, the only real difference with a non-profit or government builder is that a non-profit is not allowed to distribute retained earnings to shareholders (i.e. profits must be reinvested in the non-profit) and with government the profits go back to government coffers. Both are basically the same as a private developer rolling profits back into their business to fund the next project.

In all cases, the project level proforma looks pretty similar.

A Different Approach

So what can we as a society do to deliver more affordable housing, other than throw cash at individual projects?

Earlier I showed how providing a subsidy for affordable housing is financially equivalent to reducing the total development cost by an amount equal to the subsidy. One way to get lower housing prices at scale is to reduce the total development cost of all new projects.

On deals I’ve worked on, once you add land transfer tax, HST, planning fees, development charges, community benefits, parkland dedication, legal and consulting bills, plus the financing cost of a years-long approvals process, it can easily come to 35–45% of the cost of new housing. Roughly half of this is direct fees and taxes, and half is the cost of delays and the planning process.

If we could reduce costs by even 20%, a lot of marginal projects would suddenly pencil at lower rents, without requiring any cash subsidies. You could get there with two levers: a temporary holiday on most fees and taxes for new housing, and a planning system that gives clear, predictable approvals in months instead of years.

Some will argue this is still a subsidy. There is a difference, though, between government providing foregone revenue and cash subsidies. For example, very few new projects are moving forward today, so the city is collecting very little in development charges. If a DC holiday unlocks new projects, then the “subsidy” won’t reduce how much the city collects today (it’s already zero), but it will increase the number of projects that start, and it will create a huge increase in the future tax base.

The difference is that broad reform is simple, predictable, and available to any project that can actually get built. We’d be trading bespoke deals with negative land values for a cleaner rule set that makes the whole market cheaper to build in.

If we did that, market rents would fall, reducing the need for subsidized affordable housing in general. And with fewer people in need, government would be able to spend more generously on those who still need help.

Business Updates

Recovery Capital

Over the past couple of months I’ve been called into a number of projects to discuss new capital structures and development support for sites trying to reach construction financing. A few recurring patterns:

Most of these calls are coming from second/mezz lenders who are concerned that a senior lender might enforce after a borrower default. They’re keen to put forward a credible plan, with a capable development partner, that improves the odds of getting the project built and their capital repaid. I get relatively fewer restructuring calls from senior lenders, suggesting that most still feel somewhat secure in their positions.

Lenders are seeing far more breakdowns in basic controls than a year ago: commingled project funds, weak reporting, informal “bridge” money coming in and out without clear documentation. Sometimes it’s outright misconduct, but just as often it’s sponsors who are out over their skis and improvising. Either way, the litigation and regulatory risk is rising.

There are projects where large land loans were advanced, fees were taken out early, and very little work was done to advance design, zoning, or pre-construction. Lots of risk is being moved to lenders while sites are stalled.

In some cases, borrowers are plugging interest and carrying costs with unsecured money from friends-and-family or retail investors. On paper these are “loans,” but in a downside scenario they behave like equity that is at risk from day one.

There are a few ways that Recovery Capital we can assist in these situations.

Our first choice is to work collaboratively with the existing borrower and lenders to recapitalize the project, convert it to purpose-built rental where that makes sense, and secure construction financing together. For the right deal, we can provide the equity required to get to first construction draw, with structures that give both lenders and developers a realistic path to full recovery. Imprint typically teams up as a development partner in these cases, combining capital with rental-housing and delivery expertise. We have also developed a set of project management and financial controls that give lenders greater confidence in project execution.

In other situations, the right starting point is diagnosis. We help lenders and sponsors understand what they actually have before anyone commits new money. That can mean tightening project controls and reporting so a lender is comfortable extending a loan, or (where there are serious defaults) providing turnaround services: forensic review, site inspections, and enhanced project monitoring. Where it’s helpful, we can defer fees so lenders aren’t writing cheques while still working out a plan.

Regardless of whom we work with, our core offering remains Imprint’s development expertise: rental underwriting and deal structuring, highest-and-best-use analysis, development management, construction management, construction close-out/turnover, and lease-up support.

If any of this sounds familiar and you’d like a second set of eyes on a project, feel free to reply to this email or reach out directly. I’m always happy to look at a deal in confidence and tell you, plainly, what I see.

Imprint Development

The last month has been busy for Imprint, particularly on the advisory side. We submitted a major RFP with one of our development partners, and finalized a CMHC application with another client for a mid-rise rental building in the GTA.

We’re also looking at a couple of not-for-profit and supportive housing projects with groups that want to develop existing land holdings alongside an experienced development partner.

More generally, the land value issue I described above is really impacting deal flow. There’s a lot of land for sale, but 8/10 times there just isn’t any value under a rental development scenario.

Reading list

The best things I’ve been reading this month:

The Origins of Efficiency, by Brian Potter.

Build, Baby, Build: How Housing Shapes Fertility, by Benjamin K. Couillard.

Every Man for Himself and God Against All, by Werner Herzog.

That’s A Wrap.

I write this newsletter because I like to connect with smart people who are doing interesting things. Reach out by replying to this email or commenting below.

Thank you for reading, and have a great month.