In This Issue

How The US and Canada Fund Apartment Development

The US and Canada each have federal programs for construction and permanent financing of rental apartments. I am a real estate developer, so I’m biased but I think this is a good thing. Let me explain why.

Housing is a fundamental human need. If this need is left unmet it can create absolute havoc in a society — everything from displacement, long commutes and separation from family, to riots and rent strikes. You might be a very smart, capable person but a lot of your competence and ability to operate in the world rests on your ability to go “home” somewhere. A place to rest, prepare, and meet the needs of your family. It’s difficult to be effective at work if you are homeless. An affordable, well-located home puts your life on an easier mode, where health, wealth and happiness are more achievable.

So on the one hand, housing is a bedrock requirement for society, with many positive externalities. On the other hand, housing can be a difficult issue, politically. Democratic governments tend to enact a lot of regulations that make housing expensive to build (restrictive zoning, arduous planning processes, high fees and taxes) while also making it very difficult to operate rental housing (dysfunctional landlord-tenant courts, complex licensing regimes, and rent controls). This makes the business of owning and operating housing less profitable than it would otherwise be.

On top of this, the actual housing construction is very expensive. This is unavoidable. Even when housing used to be much less expensive than it is today, it was still very expensive relative to the incomes of people who lived in it, built it, and financed it. Real estate isn’t like software, where you can write some great code and then scale your product without incurring a whole lot of incremental cost. One unit of housing can only serve the shelter needs of one household (unless you start crowding, but we can probably agree that’s not optimal). This means that housing tends to be incrementally expensive. There’s a roughly linear relationship between cost and production.

If you are building a bunch of expensive housing, you will need a big pile of money to pay for its construction. Most of us don’t have a big pile of money just lying around. So if you are like most people (you have no pile of money) but you are also a little weird (you want to build an apartment building), then you will need to use someone else’s money. Usually that someone is a bank. Banks hate losing money. Therefore, if we make building and operating housing too expensive and risky, banks won’t lend as much money for it.

Governments are aware of this problem. There is a long history of housing not being built because of restrictive policy, so governments will often try to offset this by subsidizing housing production by other means, such as by providing financing that is better than what the private market is willing to provide. This is usually done at the federal level, which has a lot more capital than, say, the local government, and it also has the authority to operate across many jurisdictions.

The details of these programs vary a lot from country to country, depending on the political dynamics at play. I moved from the US to Canada in 2021, and have had a few years to see how the two governments approach this issue differently.

Both countries have a number of apartment financing programs available to the private sector. In the US, these are mostly, but not exclusively, administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Fannie Mae. In Canada the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) runs pretty much everything.

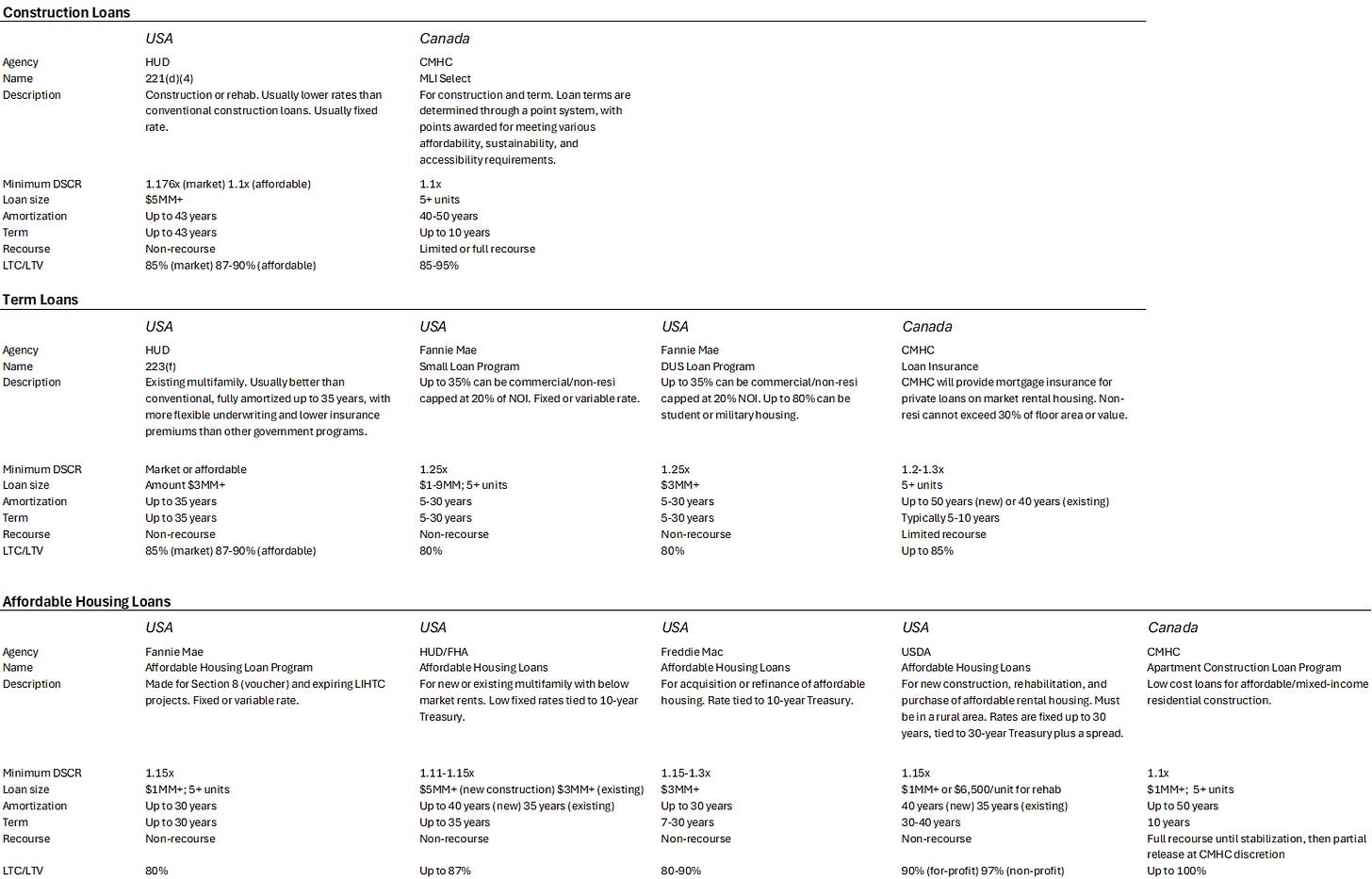

Below is a summary chart I made that shows a handful of apartment financing programs offered in the US and Canada. You will notice that the US appears to have way more options. The US is a massive country, where everything is like 10x the size of Canada — population, GDP, number of large cities, etc. So it’s not surprising that the US has a much bigger set of government housing programs. There are at least half a dozen more loan programs for specialized housing types (like elder care/dementia supportive housing, student housing, military housing) that I didn’t include. Canada manages to capture many of the features offered by US agencies, but in a smaller set of programs.

At a very high level, the US and Canada have similar approaches. Each subsidizes housing and creates liquidity by packaging mortgages into mortgage-backed securities. Each country provides government-backed mortgage insurance which allows lenders to extend loans at terms that are much better than they could for uninsured loans. These terms might include a lower interest rate, longer term/amortization, less recourse to borrowers, and looser underwriting standards. Sometimes an agency will fund projects on its own balance sheet, particularly for affordable housing.

When you get into the details, you will also notice a few big differences between the US and Canadian programs. The biggest are term, recourse, and what I will call “concessions”. While I think it’s great that Canada offers these programs to rental developers — they are literally the only way that rental deals pencil right now — I do think the loan terms could be tweaked here and there to make them even better.

Term

The term of a loan is how long the bank is lending you money. If you have a US style 30-year mortgage, your term is 30 years. If you have a Canadian style 5-year mortgage your term is 5 years. The amortization period is how long you would need to make your mortgage payments for the loan to be fully paid off.

Compared to Canada, in the US it is much more common for a loan to be fully amortized, which means that if you make the same payment every month for the term of the loan, it will be paid off at the end. In Canada, the amortization period of your loan is typically different from the term. This is a really important difference.

In the chart above, you will notice that all of the American government loans have a term that can be as long as the amortization period. This means that even if you base your loan size and monthly payments on an income projection for just the next few years, your debt service will be predictable for the entire amortization period. For example, if the bank sizes your fixed-rate mortgage payments based on a 30-year repayment schedule, you know that your payments won’t change for the entire duration of the loan. Canadian borrowers have a lot more exposure to interest rate volatility. If you secured a 5-year loan at a very low rate in 2019, with a small payment based on 30-year amortization, then you probably faced renewal at a much higher rate this year. No fun.

One thing that surprises me about the Canadian affordable housing programs is the mismatch between the term and the amortization. Affordable housing programs are, by definition, less profitable than buildings which can be rented at market rates. CMHC recognizes this, because they allow you to have higher leverage and less income compared to a market rental building with a similar loan size. This means that your margin is smaller, and your profitability is very sensitive to changes in expenses (such as interest payments). Then CMHC will loan money to these affordable housing projects for only 10 years, but using a 40-year amortization! Increasing the term to match the amortization period is something the Canadian government could do to massively de-risk affordable housing development.

Recourse

Back in Issue #04 I wrote about how loan guarantees work in development deals. I won’t rehash all of that here, but if you look at the chart you will notice that the US loans are all non-recourse, while the Canadian loans are limited recourse or full recourse. These terms have squishy meanings, but generally non-recourse means that once the developer has met her obligations to the lender, such as completing the project and leasing it up, their personal financial guarantees are no longer in effect. This means that the bank’s loan is secured by its collateral — the building itself — and not by the personal assets of the developer. It’s a question of the balance of risk between borrower and lender.

One could make an argument that leaving guarantees in place creates a stronger incentive for the developer to properly manage a project. On the other hand, as it stands, a developer could theoretically lose their home and personal savings because of a market downturn, through no fault of their own. This probably impacts a developer’s appetite to, say, build affordable housing that will be financially riskier than market housing.

Concessions

This was something I really noticed when I started underwriting Canadian rental projects. The American programs are generally set up for one of two reasons: to support the construction of market rate apartments, or to subsidize the construction of below-market apartments. Some programs can be used for both. If you meet the requirements of the program, then you qualify for the loan.

In Canada we really only have one government program for new market rate apartment construction: MLI Select. You can get conventional loans (from private lenders) with CMHC mortgage insurance, but the terms are not nearly as good. There are also programs for non-profits and co-ops, but they don’t put out much capital and they are very restrictive so we won’t discuss them here.

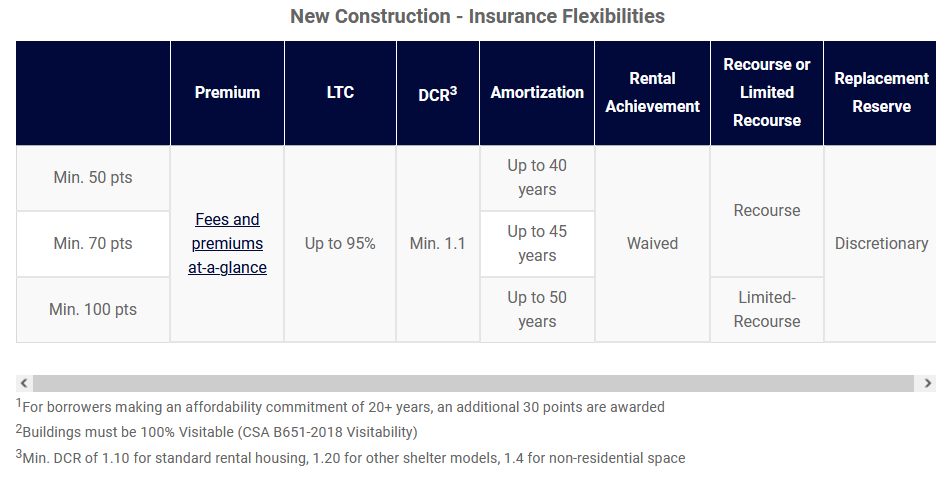

MLI Select offers increasingly favorable loan terms as you meet more strenuous project requirements. Here’s the CMHC rubric for scoring a new construction project.

And here are some of the benefits you get in exchange for different scores:

This means that to have a competitive project, you need to provide something more than just housing. You need to provide a lot of affordable housing, or you need to provide a blend of affordability, sustainability, and accessibility.

Each of those things costs money, sometimes a lot of it. This means that the government insurance programs are not optimizing for housing production — they are optimizing for housing that can also meet other policy objectives. Naturally, this reduces the number of projects which qualify, which reduces the number of projects which will get built. The government is saying: if you can’t exceed legal minimums for energy performance and accessibility, then you can’t have this financing.

In my humble opinion, it seems misguided to have these requirements in the middle of a housing crisis. If energy performance is important enough that projects should be denied the best financing on this basis, then perhaps it’s time to update the energy code to bring all projects to a level playing field. If our current codes don’t deliver sufficient accessibility, maybe we should change those too. But to require additional concessions from housing projects that our society desperately needs… I don’t get it.

If I were Canada’s Housing Czar, I would be trying to find ways of maximizing the production of housing without distraction. If there are other policy priorities, they should be structured as separate programs. For example, the US has tax credit program for the preservation of historic properties. You can layer this on top of federal loans. Certainly we could have incentives for sustainability or accessibility which could enhance a project using MLI Select, without being a minimum requirement for the housing to be built at all.

That’s a wrap.

I write this newsletter because I like to connect with smart people who are doing interesting things. Feel free to reach out by replying to this email.

Thank you for reading, and have a great October.