Does Europe Really Build For Less?

If you work in North American development or construction, you will often hear about examples of other countries building more quickly and at lower cost. This appears to be particularly true of infrastructure projects. Europeans build subways for a fraction of the cost that Canadians pay, and the evidence for this is credible and expansive. For that reason, when I’ve seen similar claims about lower European housing costs, I have usually assumed they were credible too.

But I recently came across an interesting counterexample, showing why it might not always be true that European housing is cheaper.

18 rue Pradier

This wonderful social housing project in Paris, by MAO Architectes, has been making the rounds among YIMBY circles, sparking excitement as an example of below-market housing in an expensive European city. It went viral a couple of times on social media, with lots of people fawning over its design and low construction cost.

This kind of thing is catnip for urbanists. Why? Because it’s clearly beautiful on the outside, the rents are deeply subsidized, and it was (supposedly) very affordable to build. Could there be some secret French recipe that lets them build beautifully, at very low cost? If only we could do that here!

So I started looking into this project to better understand what it costs to build social housing in Paris. I was surprised to find that this project wasn’t cheap at all! In fact, it’s probably much more expensive than a comparable project in Toronto, on an apples-to-apples basis. The interesting thing is that Paris and Toronto are subject to very different building codes and market norms, so it’s an opportunity to learn a lot about the differences in social/affordable housing production between these two very different markets.

Let’s take a tour…

First, let’s acknowledge this is a gorgeous building. I wish I could build something similar in Toronto (and I'll explain why that's not really possible below).

Here are some basic stats:

Units: 15

Gross Construction Area (GCA): 11,086 sf

Gross Leasable Area (GLA): 8,826 sf

Average Unit Size: 588 sf

Building Efficiency (GLA/GCA): 79%

A few things jump out immediately. Despite its single stair design and lack of amenity, the building is only moderately efficient at 79%. This means that there is a lot of common area/corridor as a fraction of the total space in the project. Lower efficiency is a drag on financial returns because you pay to build every square foot of space, but you only earn revenue on the leasable portion within the actual apartments. It’s a natural disadvantage for small projects.

Also, the units are a bit small, maybe 5-10% smaller than I am seeing in new projects here in Toronto. As a rule, this will increase your revenue because smaller units command a higher rent per square foot, reducing the subsidy required for affordable housing projects. This is not surprising given the central urban location, but worth noting that these are not very big units.

Design Choices & Cost Implications

Let’s spend some time looking at the major cost drivers for this project, identifying things that you would not or could not do in North America, and what the cost implications are. This is worth spending a bit of time on, because this building lacks many features that are code-required or considered basic in North America — and some of them would add a great deal of additional cost if they were required here.

Let's start outside.

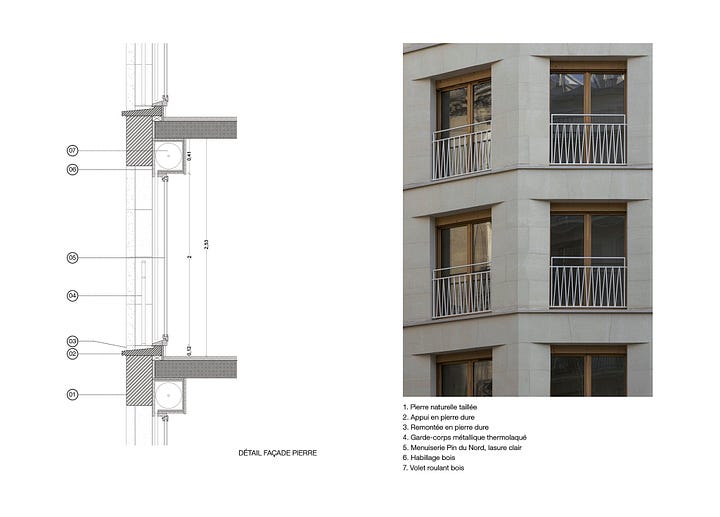

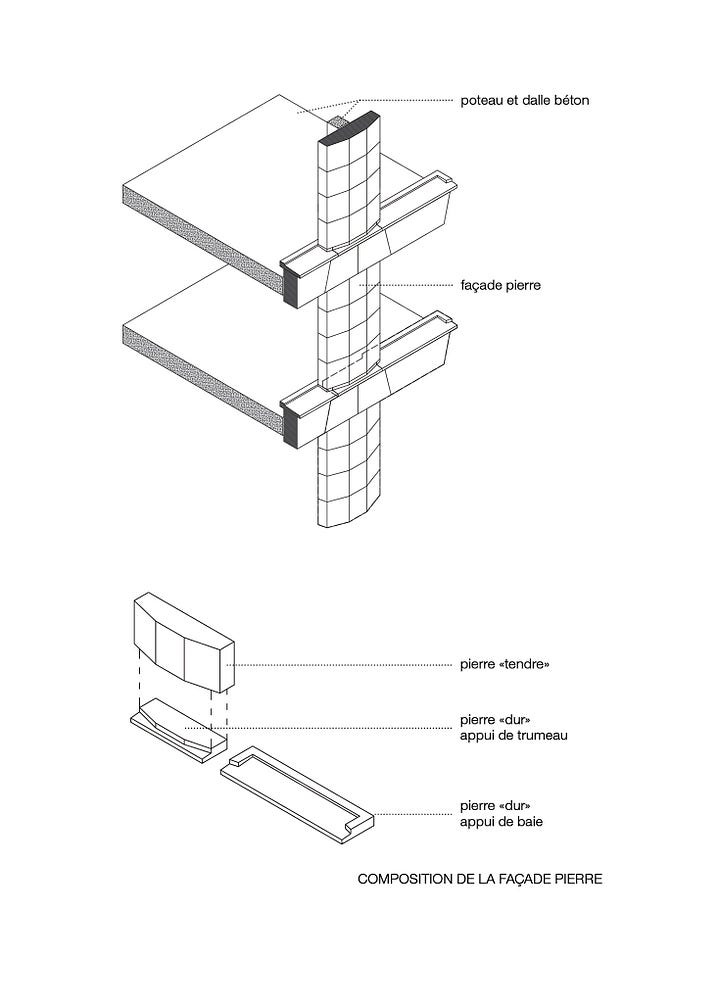

First, this building has a structural limestone facade and high-end wood windows that would certainly come at a cost premium. These aren’t code-required exactly, but there are strict heritage rules in Paris that push projects toward stone facades.

Note how the facade is clean, with no visible exhaust or intake louvers. In theory, it’s possible that they are present but artfully concealed. That would be very expensive for a social housing project. Could it be that there are actually no exhaust ducts?

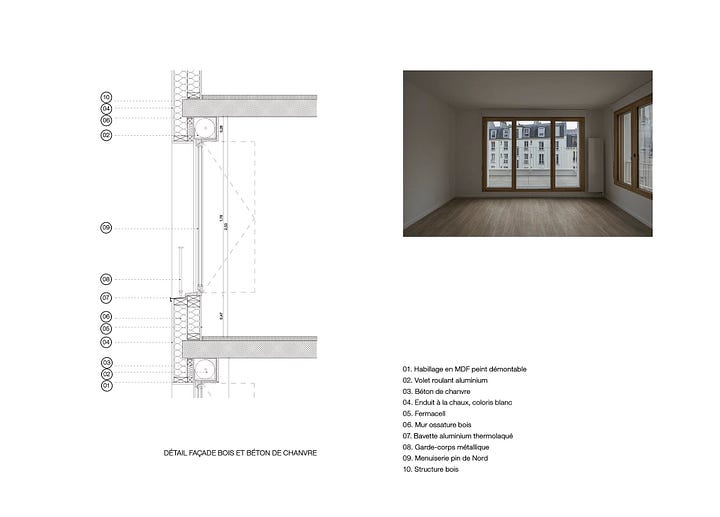

Looking inside, we see no bulkheads, ducts, or grilles. The only equipment visible is a hydronic radiator on the exterior wall in the second photo. This suggests that the building probably lacks air conditioning and mechanical fresh air supply to each living space. This would not be allowed in Canada, where both intake and exhaust must typically be active/mechanical, requiring extensive ductwork. Because the North American market doesn’t always respond well to visible ducts, we often install lots of drywall in drop ceilings and bulkheads to conceal the ducts.

In Europe, code only requires mechanical exhaust from wet spaces like kitchens and bathrooms, so it’s common to have passive fresh air supply via trickle vents at doors and windows. The exhaust is often stacked in a vertical riser, shared between units and ejected at the roof. I found an article that says this project includes individual gas boilers for each apartment, which confirms this assumption — no fresh air ducts and small, unseen intake grilles with shared roof exhausts for the boilers and wet spaces. This is a big cost savings. Worth noting that gas boilers are largely prohibited for new multifamily housing, as of the 2020 French energy code cycle.

For cooling, it’s possible that there are mini-splits not shown in the photos, but that would require a lot of exterior condensers that are not visible in the photos or drawings. And the roof doesn’t appear big enough to house 15+ HVAC units. This isn’t entirely surprising, because air conditioning isn’t required by European codes, and isn’t standard in the market. This is particularly true in older buildings. Given that this is social housing in a neighborhood that restricts visible louvers and window-mounted AC units, I am inferring that air conditioning isn’t present. It would be another huge cost savings.

Given that we saw the wall-mounted radiator, and know there’s individual boilers, I am guessing that both heat and domestic hot water are individually provided and metered. This is very efficient, cheap to build, and cheap to operate. Radiators aren’t very popular in North America, and they can be more challenging (but not impossible) to submeter with a central system.

All together, the strategy for conditioning interior space at this project is very low-cost.

What other design decisions can we see? I notice:

No ceiling fixtures or lights, except in the kitchen (and likely the bathroom). This reduces a lot of conduit and/or wiring.

No wall fixtures except in the kitchen. Single electrical outlets, whereas duplexes or even quads are more common in North America.

No kitchen cabinets or appliances appear in the photos, but the backsplash is already installed. This is common in Europe, especially upon first occupancy in a building. Tenants often provide their own cabinets.

These are all savings for the builder, some big and some small. We will look at the project’s costs below, but for now keep in mind that Canadian projects must meet more stringent code minimums, and face more costs related to fixtures and finishes due to expectations in the market. Bottom line, the Parisian project is delivering a lot less, and for a higher price.

Code Limitations

Now let’s look at some reasons, beyond cost, that we wouldn’t be able to build this in Canada.

Starting with wall sections.

The street-facing facade is solid limestone, and it appears to be uninsulated in both the photos and section drawings. This would probably not be permitted in Canada, for a couple reasons.

The architects’ website explains that this facade is designed to “breathe”, or dry naturally toward both interior and exterior. That’s generally a no-no in Canada. I’m guessing it would be hard to meet thermal resistance and air barrier continuity standards unless the stone was much thicker, included insulation in a stud cavity, and had an interior vapor barrier.

The rear facade is made of lime plaster on an insulated wood-framed cavity wall. The cavity is packed with hemp-filled concrete. I haven’t seen this detail before, and there are some interesting construction photos in the link I provided.

I am not sure whether this wall would meet Canadian code because of the wood framing. It doesn’t appear to be structural, and it is entirely enclosed by non-combustible lime plaster, but I have seen small projects that were required to use non-combustible studs in tight urban conditions. This project is more than six storeys, also in a tight infill location. My understanding is that Canadian codes usually require that buildings at this height must have walls that are fully non-combustible when close to other buildings.

One decision that really surprised me about this project is the solid wood windows. These were no doubt quite expensive, and they will require regular maintenance to maintain their clear finish. I would probably not have chosen such a high-maintenance system for a social housing project.

That said, I'm impressed that this project uses only two or three window types: a two-lite and a three-lite, likely tilt-and-turn. This design choice saves significant costs compared to having lots of different window types. It suggests a disciplined approach by the builder and design team.

It’s worth noting that the terraces are not accessible by wheelchair, allowing a simpler, cheaper concrete structure. In Canada this is allowed by accessibility codes, but is often problematic in the US.

Project Costs

Below is a budget table that I pieced together from a couple of different sources, but this site is where I got most of my information.

It was a little tricky to figure out the costs for this building, because they are reported in ways that are not conventional in North America. For example, the land was purchased for €3,950,000 but that does not include any closing costs. There is an additional “Land” cost reported of €1,139,245 but that includes site preparation (demolition, street paving, and utilities) that I would normally consider part of the hard/construction costs. I have done my best to break these out above. Any errors are my own.

All told, it looks like this building cost around €3.6 million/CA$5.76 million to build, or about CA$520 per GCA in hard costs (direct construction + site work). This is materially higher than it costs to build a small apartment building in Toronto in 2025, and these were 2018 figures!

The reason so many people thought this project was inexpensive is because on social media people were focused on a reported CA$318,000 cost per unit, which would be pretty good. But that number excluded not only the land cost, but a lot of hard costs that were reported as part of the acquisition price. The total cost per unit is actually CA$861,206.

Even with my corrected budget, the per-unit numbers are a bit misleading. There are no amenities or loading/leasing/back-of-house spaces in this building that tend to drive up the per-unit cost of North American projects. I think price per square foot is a better metric for comparing costs across jurisdictions. And this project cost CA$1,165 per sf of GCA! This is extraordinarily expensive, particularly for affordable housing.

Financial Returns

The project includes four “social housing” or deeply affordable units, and 11 intermediate rent units. I pulled the latest rent caps for 2025 from this site, so we can estimate the income for this project. The original sources are all in French, so I translated them and audited the numbers to make sure everything is accurate.

If we assume a 30% expense ratio (which might be low for social housing), we arrive at a Net Operating Income (NOI) of CA$203,633. This is a yield of only 1.58% on the total development cost, which means the project would have needed massive subsidies to attract capital and development expertise.

And sure enough, that’s what we see in the published capital stack:

The developer contributed 15% equity for this project, and received another 2% in the form of a grant from the state. Almost all of the remaining funding came as debt, both subsidized and market rate. Interestingly, this is similar to the leverage that you can get with, say, CMHC MLI Select financing today. I was not able to find the terms for this debt, so I can’t say what the cash flow looks like. But I would be very curious to know, because with 25-year amortization, even a 1% interest rate on $10.7 million in debt is more than the NOI of this project. My guess is that there must be a longer term for the conventional loan than the government loan, and maybe a forgivable component.

[The upshot for policymakers is this: if you want to provide very low-rent apartments, you need to cough up a lot of cash to just barely break even. There is no free lunch, no magic recipe for cheap social housing in urban infill locations with energy, heritage, and other requirements layered on. The math doesn’t really change much whether it’s the private sector building the housing, or a nonprofit, or the government. What the private sector calls “profit margin” is required by banks (and government agencies like CMHC!) to ensure there is enough free cash flow to service debt, and to absorb unexpected costs during development.]

Overall, this is a beautiful building that we could probably deliver for much lower cost in Toronto, if we were allowed to cut certain items like mechanical ventilation, air conditioning, and finishes like kitchen cabinets. Conversely, if they built to Canadian standards in Paris, it would cost much, much more.

Where they’ve got us is on beauty — I can’t think of a single small project in my city that looks this nice.

That’s A Wrap.

This month marks two years since I started this newsletter. It has been a great experience. One of my favorite experiences is meeting someone for the first time, and hearing that they are regular readers. If you have any feedback for me, I would love to hear it.

Reach out by replying to this email or commenting below.

Thank you for reading, and have a great August.

Really cool analysis, thank you for sharing

Do you have any ideas what factors most contributed to the project costing so much more? Higher materials costs? Labor? Aside from the windows and maybe front exterior materials, everything you described sounds like it would make the project cheaper, so the final price/sq ft is surprising

Bless you for digging into the details. We need more of this in the weeds work to ground our international comparisons.