#23 - Developer vs. Dirt-Flipper

Who decides what “developer” really means?

In This Issue

Developer vs. Dirt-Flipper

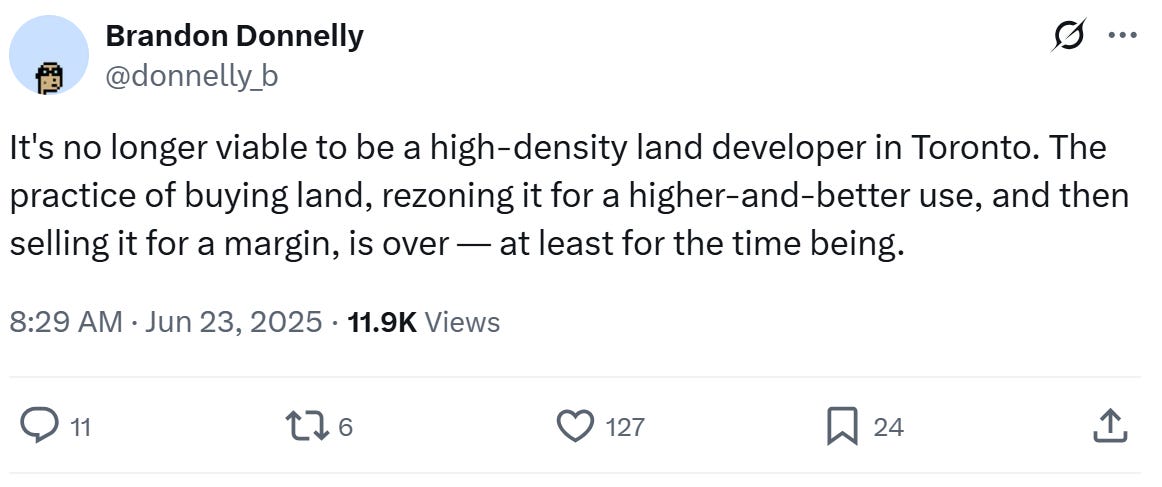

A couple of weeks ago, there was a very entertaining online debate sparked by this post:

Some people argued that you’re only a “developer” if you physically construct housing. Others claimed that someone who entitles land (i.e. gets the government approvals required to build housing) is a developer, even if they sell the entitled land and never build anything on it.

In a way, this is a fun, low-stakes debate. The stakes are low because it doesn’t actually make a difference who gets to call themselves developers. There is no license, credential, or membership in a professional association that is required to be a developer. The barriers to entry are very low.

On the other hand, there is a serious question about how developers should conceptualize their role in the market, because it has a big impact on the quality of the industry and the buildings it creates.

Among my friends who actually work in development — whether they build or not — most agree that doing land entitlement counts as development. Let’s call this camp The Big Tent, because they are liberal with the label. The people who say that entitlement work doesn’t count as development are more likely to be professionals who do neither entitlement nor construction, like architects, real estate agents, and planning consultants. Let’s call this group The Small Tent, because they want to dictate who is allowed in the club.

The reason people actually care about this is, in my opinion, mostly about status and cultural currency. Think of it like packing a suitcase. Packing isn’t traveling, but traveling requires you to pack. It is possible to do a lot of travel while having someone else pack your bags, and this has no bearing whatsoever on anyone else’s life. Nonetheless, certain people will judge you for speaking publicly (say, in a travel blog) about your travel experiences, while having someone else do all of your packing and planning. I think that’s kind of what’s happening with The Small Tent.

Let me explain how I think about this debate, on the actual merits.

When I learned the business in the US, development was generally considered to be the full lifecycle process of creating buildings. That process included conception, finance, design, entitlements, construction, and operations. At the same time, most people called everything before construction pre-development. This implied that development started with construction. If a company didn’t build housing, but instead focused on just purchasing and operating existing buildings, they were definitely not called a developer, but rather an owner. If someone was not the owner, but rather a consultant working on behalf of the owner, they were an owner’s rep. Unless they were explicitly called an owner’s rep, everyone would assume that the developer was also the owner. Altogether, the concept of development was closely tied to the ownership of projects and the construction of new housing, and this necessarily included pre-development activities.

In Canada, my experience has been a little different. Development usually refers to the planning/entitlement process rather than the full lifecycle. Someone who gets planning approvals is a developer and the person who builds buildings is a builder. A builder can be a developer, too, if they handle the entitlements in-house. Just as in the US, someone who owns but does not build is not considered a developer, and it is also generally assumed that a developer is also the owner.

In both countries, firms tend to specialize in specific parts of the process. This is because it’s hard to excel at all parts of the process. For example, in my US company we did everything up until construction in-house. We used a third-party general contractor to build, but I was at all of the construction meetings and made budget decisions. We also used third party property managers, but I was the asset manager who approved pricing changes, the marketing strategy, and monitored performance. So while we would delegate day-to-day responsibility to other firms, I was actively involved at every step of the process. My consultants and contractors called me a developer, or the owner on all of these projects.

Why is this important? Well, in a way it’s not important at all. As I said, there are no strict requirements for becoming a developer. At the same time, I believe that how a developer conceptualizes their role will lead to different outcomes, and some outcomes are better than others.

An orthopedic surgeon can be really good at what they do, but if they forget basic medicine (e.g., sanitation, drug interactions) they could have blind spots that may put patients at risk. To be the best possible practitioner of medicine, they need to master and maintain the basics while honing more specialized skills. Similarly, someone can specialize in obtaining planning approvals, and they might get really good at getting something approved. But if they have no knowledge of construction or operations, their designs won’t be very efficient to build, and the buildings will be harder to operate. Their pool of buyers will be smaller, and they will get a lower price for their entitled land. Even if they get approvals more quickly or get more density than other developers, they won’t necessarily be “the best” in the context of the full development lifecycle.

So if we tried to sketch a Platonic ideal for what a developer is, we might say that the ideal developer would have a solid understanding of, and experience in, all phases of development, including construction. This person will have a holistic perspective that attempts to optimize across all phases of a project rather than just one part.

In this way, The Small Tent has a point.

But at the end of the day, I am personally in the Big Tent camp. While I believe that someone who only does entitlement is not likely to be the best developer (in the sense of our aforementioned ideal), there is lots of room in the market for people to create value in different ways. Entitling land is a necessary and challenging part of the development lifecycle. Most of the time, it creates real value… sometimes even most of the value. This can be precisely calculated as the difference between the market price of the land before and after entitlement.

In Brandon’s original post, he is pointing out that until a few years ago, in Toronto entitlement used to be the highest value-add part of the development cycle. Today, that value has shifted to construction and operations. The pendulum may swing back one day.

Business Updates

Imprint has raised some money under the Recovery Capital banner to help stalled or distressed development projects get back on track. The market response has been positive, and this has given me a chance to observe the distressed segment of Toronto’s land market, up close. A few trends I am seeing right now:

Equity continues to be selective. There are lots and lots of sites for sale right now, and not a lot of buyers. If you are trying to raise equity, ask yourself: why should someone invest in your deal versus all the others that are available? Just because you have spent $200 psf to get your site entitled doesn’t mean that investors will pay $200 (or more) for it. Many sites today have $200 in basis but are only worth $50. To raise additional equity today, new capital often needs to earn a pref and sit in front of existing equity. This might sound ugly, but it is better than losing a site entirely.

Time is killing lots of projects. People are waiting way too long to address financial problems. I have received a few calls from borrowers who needed millions of dollars in less than two weeks, because they were about to lose a site to receivership. As a rule of thumb, it takes 6-12 months to negotiate a workout strategy and it could be even longer to execute it. It’s best to start these discussions early — around the time of a loan extension or forbearance, or when you have 12-18 months of remaining capacity to pay the interest on your loan.

Condo-to-rental conversions are complex. They take time, money, and a completely new business plan. I have seen several projects fail to pivot because the owners didn’t want to make the necessary changes to their design, budget, schedule, or deal structure. In each case, there was supposedly a JV partner who would put up all the equity for a rental conversion, without requiring any of these changes… but they didn’t end up closing. Unfortunately, these developers didn’t have a contingency plan for when those negotiations fell apart.

Bad proforma inputs are rampant. First-time rental developers are especially prone to this. Just because CMHC will accept your assumptions doesn’t mean you should do a given deal. These loans tend to be high-leverage, low-margin. If you fail to hit your proforma rents, or if your expenses are higher than anticipated, or you have significant cost overruns, then you could lose everything because you default at completion or loan maturity.

Rentals are missing DSCR. Some buildings are failing to hit their proforma rents, and running high on opex. To make matters worse, poor financial controls and unexecuted change orders are leading to projects that run out of loan proceeds long before they are complete. Borrowers (even ones who were once considered well-capitalized) don’t have the equity to bring these loans into balance. If the lender demands more equity and the borrower can’t pay, then cash stops flowing to trades and projects grind to a halt. But if the lender allows the borrower to defer equity contributions, there is a strong incentive for the borrower to stop reporting accurately, and to hide problems.

Lenders are giving up. Last year, lenders seemed happy to keep extending loans, as long as borrowers were paying interest. Interestingly, many lenders were also happy to ignore minor, non-monetary defaults or breaches of covenant. That is now changing. Lenders are quietly tracking compliance to build a stronger case for receivership proceedings, and are indicating they will no longer extend loans without a credible path to construction. Even for good clients that they want to keep working with in the future.

What We Are Doing About It

Recovery Capital was started specifically to deal with situations like these. We provide debt or equity to projects that are fundamentally sound, but need cash to get back on track. We also provide expertise in development management and deal restructuring to give lenders the confidence to continue supporting these projects. Our goal is to keep projects out of court, and to protect reputations.

Who should reach out to us?

Lenders with loans they can no longer extend, where a default is likely in the next 12 months, or where the borrower requires execution support.

Debt brokers with clients who are struggling to obtain financing.

Borrowers who want to convert their condo projects to rental, or who are heading toward occupancy on their first rental project.

Equity investors who are experiencing capital calls or halted distributions, with an unclear path to project completion.

Receivers and other insolvency professionals who need technical expertise to reposition challenged projects. We can provide stalking horse bids for the right opportunities.

That’s A Wrap.

I write this newsletter because I like to connect with smart people who are doing interesting things. Reach out by replying to this email or commenting below.

Thank you for reading, and have a great July.

I am enjoying your news letters, you are bang on with what is happening out there.

The government is raping the entire development process with fees and taxes.

Being in Real Estate for 37 years as a Realtor and specializing in development, new home sales and also a top resale agent I have a good handle on the market.

I have a plan that could create more affordable housing, get our youth into the market, help sell at least 10 to 20% of any new home site to kick start it creating jobs.

It would not cost the tax payers a penny and would not need to hire any more government to implement it.

The lawyer on closing of each deal would just need some paperwork signed.

Keep up the good work you definitely touch on all the problems and issues.

Unfortunately the government has created the problem and has no interest in fixing it.

Being in Real Estate industry for over 45 years and work only with Developers and builders in low rise market. High rise was good when market was good if you look past history of high rise investors is always been high risk because of one high multi units closing within same time frame if you are caught in a down tie market with high debt then hole project will fail.Low rise builders will build what they can sell few will always get in trouble due to over leverage. Developers are as important to builders both have different role and financial obligations. Land development takes years to get approvals from red tape at Municipal level, TRCA and other agencies, where builders is out of the project with in 2 years