Sponsor-Based vs. Asset-Based Lending

This month we have a guest contributor helping me tackle a big topic in Canadian housing and development. Rob Borowski is currently Vice President of Business Development at MarshallZehr. He has spent the last decade working across Canadian lending, including commercial, diversified, and real estate finance. He contributed extensively to this piece based on his experience with both Canadian and US lending.

When I moved from the US to Canada and started looking at development deals, I noticed a lot of differences in the loan terms for typical multifamily projects.

Some were obvious from day one. Canadian lenders require much stronger guarantees from a developer, whereas in the US, non-recourse lending is much more common. I wrote previously about these types of guarantees. They signal that Canadian lenders are less willing to take on project risk and prefer borrowers with enough assets to absorb potential problems. This is very reasonable — if I were loaning a bunch of money to someone, I might also want to know that they had the financial ability to address unexpected issues. But it also shapes the market in specific ways. It favors large, well-capitalized firms over small, scrappy operators. It probably makes the market less dynamic and competitive, but more stable and predictable. Tradeoffs.

Other differences only became clear once I was working on active construction projects. Canadian lenders tend to be more tolerant of cost and schedule overruns. Until very recently, lenders were happy to gradually increase a loan’s principal amount during construction, as long as a cost consultant could credibly argue that the value created (through construction itself) had kept the overall loan in balance. I had never seen this before moving to Canada. In fact, I’d never even heard of a cost consultant! And outside of a major design change, I had never increased a project budget more than once.

I think this is partly an artifact of structural differences between the rental and condominium businesses. As we’ve discussed before, in Canada condominium has dominated since at least the late 1980s, while in the US rental housing is the predominant form of multifamily housing.

In a condo project, the loan covers costs through construction and the developer's profit comes out of the last 30% of condo sales. That creates a bunch of free cash at the end of a project. Cost overruns and trade claims can be settled using that cash, without involving the lender. Rental projects are different. There’s usually no immediate sale or liquidity event at the end of construction. So any overruns must either come out of the developer’s pocket as additional equity, or from the bank as a loan increase.

My theory is that the condo market was so profitable, for so long, that Canadian lenders got used to developers settling project finances at the end of a deal, rather than on a monthly basis.

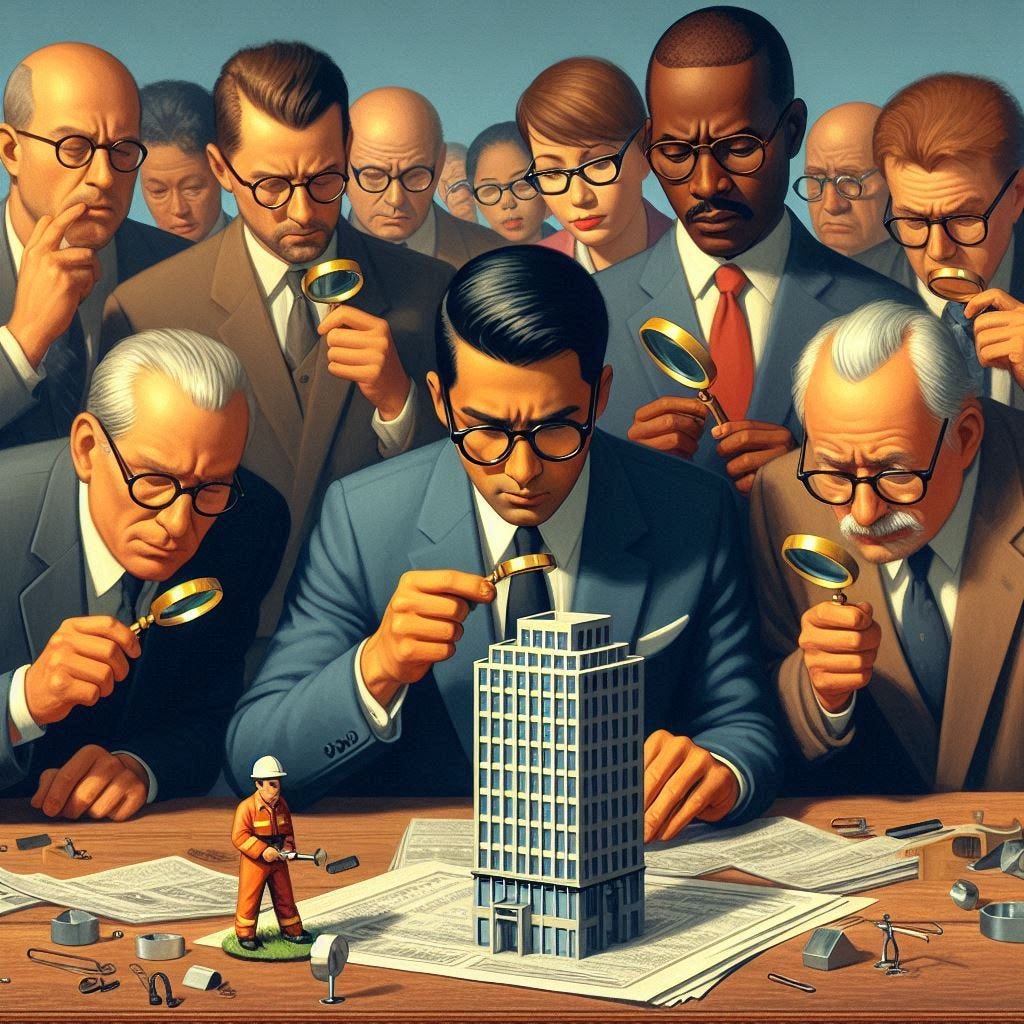

What does that look like in practice? In my experience, both debt and equity in Canada take a more hands-off approach to project monitoring, and enforce fewer standards for financial and management controls. On my US projects, I had to submit bank statements and cash reconciliations for operating accounts. This way the bank or equity investor could confirm that I was spending money on the things I said I was. In Canada, that level of transparency is rare. In the US, I had on-site project monitors who inspected construction every month and sent reports directly to my bank or equity partner. I never saw those reports. In Canada, cost consultants review monthly draw packages, but they normally spend little time on site and don’t report independently.

Bottom line: Canada has a different philosophy of risk. In some ways, it’s more conservative. In others, it’s more permissive. Much of the difference comes down to relying on sponsor guarantees instead of digging into the details of each project.

The Sponsor-Asset Continuum

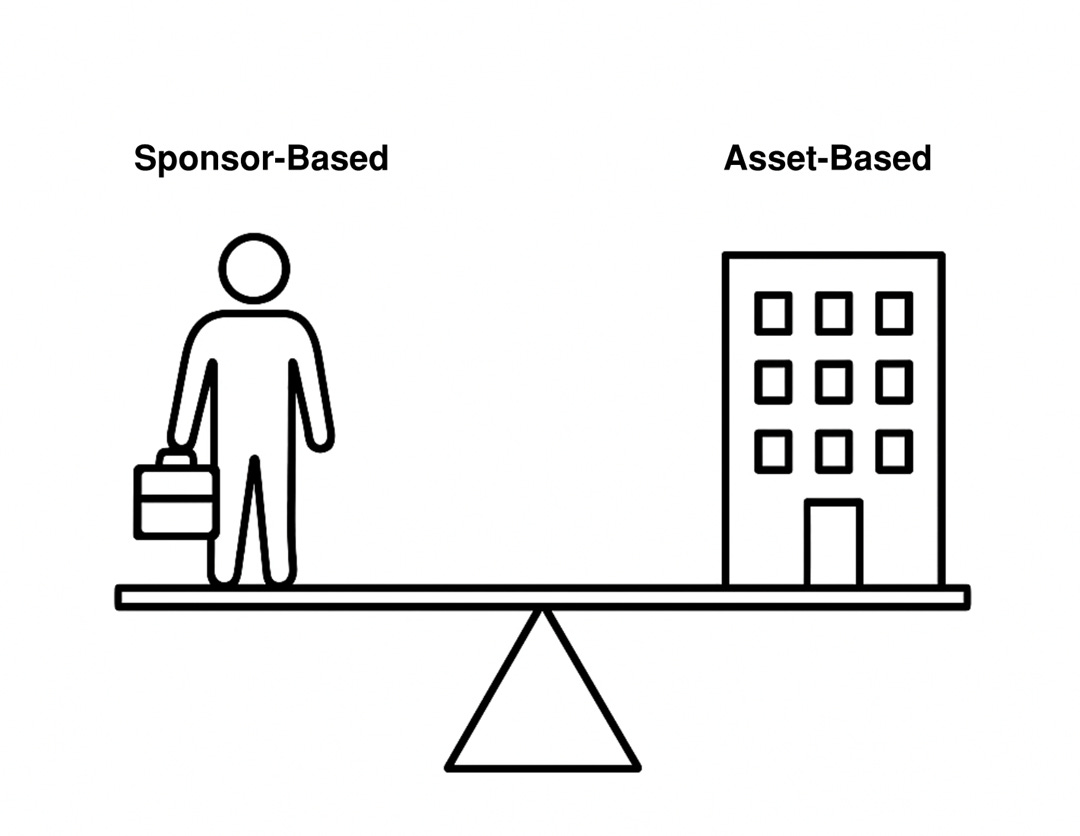

One way to understand this difference is to imagine a continuum between sponsor-based lending and asset-based lending.

At one end, lenders focus on the sponsor: the strength of the borrower’s balance sheet and their track record. At the other end, lenders rely on the intrinsic value of the asset itself. In real estate, that means the land and building.

Most lenders sit somewhere in the middle. They look at both sponsor strength and project fundamentals. Whether an institution leans one way or another depends on how they make decisions at the margin. Will they go with an established borrower just because of name brand, despite aggressive assumptions in the development proforma? Or will they lend to a new developer with a weak balance sheet because they think the deal is solid?

This orientation is usually informal. Most often it reflects the internal wiring of the credit or risk team. Who gets the final vote? What deals have blown up in the past? What kind of failure are they afraid of repeating?

In some shops, you can trace this posture back to a single person. A conservative CRO or VP of Credit who got burned on a public insolvency can shape risk behavior across the platform. Over time, these preferences become institutional muscle memory. You see it in which deals get approved, how diligence is scoped, and how flexible the terms are.

Whether a lender leans toward the sponsor or the asset isn’t written down, but it shows up everywhere in how they work.

The Canadian Vs. US Approach

Before 2020, many Canadian lenders (especially alternative/private lenders) were comfortable lending against the asset. The prevailing question was: Would I want to own this building?

That mindset works best when markets are rising and lenders feel confident about recovering all of their principal and interest through receivership or power of sale. But between 2020 and 2024, the focus shifted hard toward sponsor strength. This made a lot of sense in the context of the global pandemic, which led to runaway cost escalation because of inflation, supply chain challenges, interest rate volatility and shifting consumer demand patterns. Lenders started to ask a different question: Can the borrower fix any problems with their own cash?

Take construction loans. Lenders used to be comfortable lending to a project with an experienced contractor on the team, even if the developer didn’t have much construction experience. The banks figured they could step in and finish the project with the same GC if the borrower defaulted. But during the pandemic, contractors stopped honoring contracts because of rapid cost increases and other challenges, and banks lost confidence in their own ability to finish projects on budget.

As a response, underwriters went from looking at, say, a borrower's bank account balance, to running detailed portfolio, contingent liability, and cash flow analyses. Contingent liabilities are things like personal and corporate guarantees, letters of credit, indemnities, completion guarantees, and non-debt guarantees, such as commitments to a bonding company. Lenders also wanted to know about uncalled commitments, like pending capital contributions for future projects. To put it another way, lenders moved away from taking a snapshot of the borrower's financials to doing a comprehensive stress test of a borrower’s entire financial profile. Of course, this adds lots of underwriting time.

All of this coincided with lenders lowering the amount of leverage they would extend, and demanding higher contingencies in project budgets. Sometimes these contingencies had to be held in trust rather than managed by the developer within the project budget. Altogether, the cost of financing grew and the amount of available credit fell.

Meanwhile, in the US, the lending market looks quite different. Non-recourse lending continues to be the default for many loan types, with “bad-boy” carve outs. These are provisions in the loan docs where the borrower indemnifies the lender in cases of fraud and gross negligence. This kind of structure is more about policing behavior more than guaranteeing project performance.

US banks are also much more likely than Canadian ones to have asset management arms that are ready to step in and take over troubled projects when necessary.

Why are US and Canada Different?

One theory: Canada has less scar tissue.

We in Canada haven’t experienced a true real estate recession since the early 1990s. The global financial crisis barely touched Canadian housing. That’s often chalked up to our conservative banks, but it also reflected Canada’s smaller mortgage balances and relatively affordable homes.

In the US, leverage was much higher for a typical loan, underwriters did not have to “stress test” individual borrowers, and many borrowers were carrying multiple properties. Some people had millions in mortgage debt with very little income. A totally different picture from Canada. After it all blew up, US institutions had to build expertise in restructuring and asset management in order to clean up all the bad loans. But the playbook didn’t need to be rewritten in Canada because we didn’t experience much distress.

Recall that credit culture is downstream of a firm’s principals. Canada’s lending community is dominated by leadership who haven’t been through a recent cycle, and most firms don’t have the organizational memory for how to deal with it. Instead of working through distress, many lenders are trying to avoid write-downs by waiting for a market recovery.

There’s risk here, because lenders are carrying a larger number of increasingly distressed loans on their books (even if they never technically issue a notice of default to borrowers) rather than cutting losses and moving on. This means that capital is locked up in unproductive assets instead of being redeployed toward new, viable projects.

Why It Matters

This would be an interesting academic exercise if we weren’t in a housing crisis. But we are! High housing costs are dragging down Canadian productivity, slowing household formation, and distorting job markets.

The best way to lower housing prices is to build lots of housing. But building lots of housing requires lots and lots of money. And unfortunately, the sponsor-first lending culture we’re experiencing makes capital scarcer and more expensive. This is because equity is the most expensive capital in the stack. Requiring more of it (by reducing leverage) raises project costs and locks out smaller builders.

That leads to less housing and higher prices.

What Can We Do?

For lenders

In some ways lenders might want to become more conservative, and in other ways more permissive. Continue to question borrowers, and stress-test their proforma assumptions with current market inputs to protect yourself on the collateral side. Continue to codify dual guardrails, by underwriting both the sponsor and asset attributes.

At the same time, try thinking more like an asset manager with the ability to step into a project when necessary. Sometimes good deals get stuck in a bad market, and there is opportunity to create value there. Consider setting up an AM desk or partner with someone who has one, so that you can take title and advance projects with more confidence. (Imprint can help with this — call me!)

Remember that sometimes the borrower relationship you have may not be the best one to advance a specific deal. For example, I have seen lenders with distressed high-rise loans invite their industrial or low-rise developer clients to bid off-market. Usually this has led to long delays and ultimately no deal.

And finally, time is not your friend in distress situations. Keep moving forward, one step at a time.

For Borrowers

Preempt the diligence gauntlet. Be prepared to answer questions about your liquidity, and be forthcoming with information. It’s common for people to spend months on an application and never get the financing.

Partner where necessary for expertise and covenant. CMHC in particular is becoming more skeptical of first-time rental builders. Be proactive about building a credible team, and providing good security. Make it easy for credit committee to say “yes”.

Shop for lenders who are incentivized to complete buildings, not just those with the lowest rate or quickest funding. Your lender sees a lot more deals than you do, and can provide more value than just money.

For policymakers

All levels of government should recognize credit friction is a policy variable.

The federal government has the most power when it comes to the credit markets. They can set CMHC policy, backstop the agency against losses, and serve as a buyer of last resort for mortgages.

The federal government also has the power to create a new agency to compete with CMHC, with a mandate that extends beyond providing mortgage insurance. For example, it might function more like Fannie Mae in the US, purchasing commercial mortgages, securitizing them, and guaranteeing mortgage-backed security (MBS) payments. This would have the dual benefit of reducing CMHC’s market exposure, and providing fresh liquidity to a struggling market.

Provincial governments have the most power when it comes to controlling project costs. I estimate that between 40-50% of a typical project’s cost in Canada is either direct payments to government in the form of fees and levies, or the costs of delay and complexity due to planning and construction regulations (mostly unrelated to building code). Premiers should be focused on reducing the cost of construction by 30% or more, which would have a far larger impact than any intervention that we are used to hearing about, like modular construction, pre-approved plans, development charge deferrals, and so on. Most of this could be accomplished through a temporary or permanent reduction in taxes and fees.

Reducing costs would have a huge impact on the number of viable projects, and the financing available to them, by reducing the equity (and guarantee) required for any given deal.

Municipal governments have the most power when it comes to time. They are 100% in control of how long it takes to obtain planning permissions and building permits. Many jurisdictions around the world can approve housing in a small fraction of the time that it takes in Canada, without sacrificing safety or environmental standards. So don’t let anyone tell you it isn’t possible.

This is low-hanging fruit, because delays not only increase uncertainty (and therefore increase the returns that investors expect in exchange for taking on the additional risk), but they also increase the costs of financing itself. It means more consultant work, and more construction cost inflation between the date when a project is underwritten and when a building is completed. All of these costs must be financed in one way or another, and that means municipal rules have a huge influence over how much projects cost and how lenders think about their business. Riskier development timelines mean that lenders will want to favor well-capitalized, large developers doing larger projects, over smaller developers who can respond to demand and provide housing in shorter time horizons.

Canada’s pivot to sponsor-based lending was a natural and sensible response to moment in time. But if we’re serious about building our way out of the housing shortage, we need a system that rewards good projects—not just strong balance sheets.

That’s A Wrap.

I write this newsletter because I like to connect with smart people who are doing interesting things. Reach out by replying to this email or commenting below.

Thank you for reading, and have a great June.