#19 - Is It A Good Time To Build Rental Housing?

It depends on who you are and how you underwrite.

Is It A Good Time To Build Rental Housing?

This is a tough time to be a real estate developer in Toronto.

The predominant forms of housing in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) for decades have been single-family homes in the suburbs and condominiums in urban areas. But as of last year, there was a 69% decline in new home sales compared with the ten-year average. And condo launches are also down by around 70%.

It makes sense that condo developers are thinking of pivoting to rental development. As I’ve written about before, this is easier said than done. Nonetheless, I think it might be a very good time to invest in GTA rental housing. I have three general reasons.

Macro Trends

The Rise of Rental

Risk/Reward Balance

Let’s quickly look at each.

1. Macro Trends

As we just mentioned, new housing starts have collapsed and that means that after current construction projects deliver, there will be a years-long period with very little new supply. Starts fell off a cliff in late 2024 and early 2025. The typical multifamily project takes 2-3 years to build, so the impact will be felt in 2027 and later.

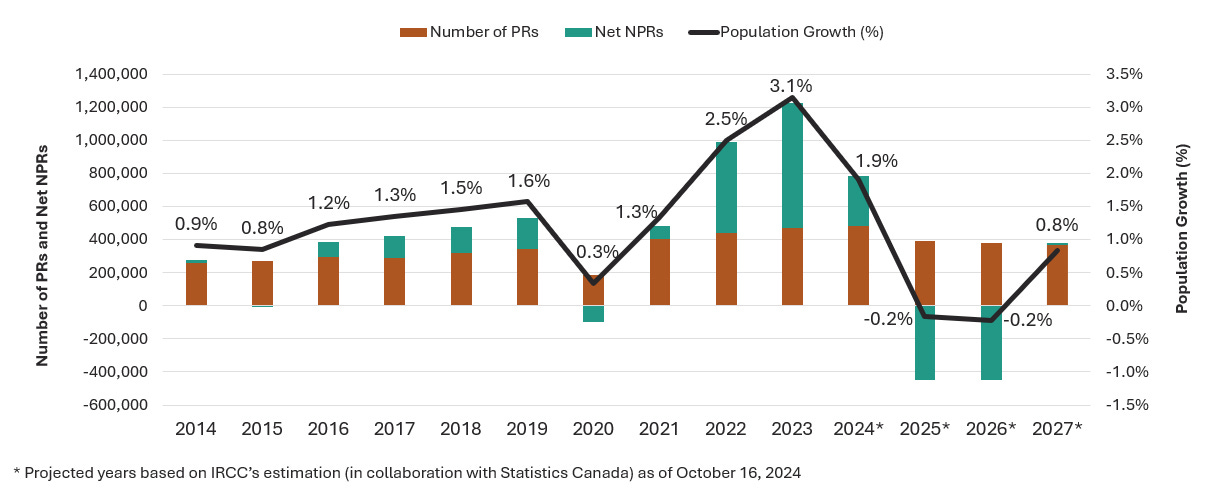

This is important for a few reasons. For years Toronto has been one of the fastest-growing cities in North America, and this is driven by immigration. In the long run, barring a seismic shift in public sentiment, the Canadian government plans to grow the national population a lot — at a rate of around 1% or 400,000 people annually.

When immigrants come to Canada, they overwhelmingly go to only a few places. Around 40% of them come to Ontario, and most of those people come to the GTA. This is because the greatest economic opportunity is here — Toronto creates 20% of GDP with 7.6% of the population.

Interestingly, virtually all of the Toronto region’s growth is driven by immigration. The region is actually losing population among existing residents, who are heading to other provinces and other parts of Ontario.

The upshot of this:

There will be a big drop in new supply starting around 2027-28.

At exactly this time, the Canadian population will start growing again between 0.5-1% per year through immigration.

The GTA will continue to attract an outsized share of these newcomers. These new Torontonians will need a place to live, and this will place intense upward pressure on housing prices and rents.

2. The Rise of Rental

The rise and dominance of the condominium in Ontario has been, in my opinion, purely an artifact of government policy. In most cities around the world, multifamily housing = rental housing, with condominium making up a small portion of supply. Toronto is an outlier.

Over the last several years, there has been a recent resurgence of interest and investment in rental housing in the GTA. Government has been shifting policy back toward encouraging rental construction. For example, rent control (which has typically allowed at- or below-inflation rent increases in Ontario, and which at one time included vacancy control) was removed from new construction in 2018. Harmonized Sales Tax, equal to around 9% of total project costs, was recently removed from new rental buildings. Development Charges (excise taxes on new housing supply) have been set relatively lower for rental units compared to condo units in some major cities. CMHC now offers attractive financing for rental projects, using programs like MLI Select and ACLP.

More pro-rental reforms are being discussed and proposed all the time. It feels like rental housing is catching some tailwinds, at least from a policy perspective. I am cautiously optimistic that this trend will continue.

Furthermore, there is very little land available for single-family development in the region. This means that future supply increases will generally come in the form of multifamily housing in existing urban areas. As has happened in virtually all desirable urban areas around the world, this will increase the proportion of households who rent, with most of the shift happening at higher income brackets.

Think of a family that can afford a 3-bedroom, $1 million home in a far suburb, with a 1-hour commute each way, at a monthly mortgage cost of $4,500 plus insurance, taxes and maintenance. That same family could rent a 2- or 3-bedroom unit in a brand new project downtown for less than $4,500, with no additional expenses, and have a 15 minute commute by train or foot. This is your marginal new renter, and daily life for this cohort will gradually start to more closely resemble places like New York.

3. Risk/Reward Balance

This is a nuanced point, so I will attempt to make it carefully.

Two truisms to keep in mind:

Today’s depressed development market in Toronto is totally normal, historically speaking. This is the contraction phase in a credit cycle. In a downturn, dollars tend to flow based on sentiment, rather than fundamentals. At this point in any credit cycle, there are usually many good deals to be done, but people are risk averse and capital is scarce.

In any investment, you want to structure your position so that under a wide range of circumstances, your potential upside is larger than your downside.

Now let’s step back and look at the Toronto rental market in particular. Because the investment yield on rental housing is so low, investors and builders often get nervous about their profit margins. This is rational. If your margin is thin, you have a lot of downside risk from unexpected costs or market fluctuations. How should you think about relative payoffs with uncertain future conditions?

Here’s my approach. I will underwrite a project using today’s market conditions as inputs. I am conservative during this phase, using prevailing hard costs, soft costs, operating costs, and local rents in my model. Then I add in healthy contingencies to cover things that will go wrong, because they always do. This is, roughly speaking, my worst case scenario.

I say worst case because if I have properly scoped and managed my project, I should not have very large swings in any of the variables that I control, most of which have to do with project costs. For example, ideally I won’t start construction until I have locked in my pricing through a GMP contract. There is always still some risk — sometimes there are unforeseen conditions, particularly during excavation or during renovations. But generally speaking, a competent development manager can control costs within a reasonable range. If you are consistently experiencing 20% cost overruns on your projects, you will find the problem in the mirror.

Therefore, barring an economic depression, a war, or an asteroid impact, my first proforma should reflect the investment performance of a deal under poor market conditions. Of course, being conservative during this phase means that most projects don’t pencil. They do not provide sufficient returns to justify the risk of going through the development process. But some deals in very specific submarkets still work, and those are the ones that I will take to the next step.

Next, I like to spend my time thinking about risk and reward sensitivities. This is where things get more interesting. As we discussed above, we are in an environment where the following things are all true:

Very little new housing is being approved and constructed (i.e. almost no new supply until at least 2028 and maybe longer).

Starting in 2027, we will continue to see at least 350,000 new immigrants per year (i.e. lots of new demand for rental housing).

Most of those immigrants will end up in and around Toronto, because that’s where the economic opportunity is.

All this means that the conservative inputs that I used in my proforma, based on today’s depressed market, are very unlikely to remain constant over the next few years. If anything, I expect supply to crash and demand to jump, leading to rapid escalation in rents, and further political pressure for regulatory and land use reforms.

If I’m right, that means there is a lot of potential upside for people who invest in rental projects today — with one big caveat.

And I can’t emphasize this enough. My worst case scenario assumes you are a highly competent rental development manager who can control cost and schedule, and then efficiently manage building launch and lease up. If this describes you, then when starting rental projects today, your downside may be much shallower than your upside. (If you have never built and operated a rental building before, this is not you. Sorry.)

Let me provide a quick illustration, using a $100 million project. For the sake of simplicity I am going to ignore levered returns (returns which are enhanced through the use of debt) and the impact of time on returns, usually expressed with an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) calculation.

To achieve this proforma in today’s market, you really need to be in downtown Toronto. People are claiming to achieve these rents in other submarkets, but generally when I look at property websites and calculate the value of various leasing incentives, the effective rent is lower than this. That’s the reality on the ground, today. In my new rental development proformas, I usually carry average annual rent escalation between 2-3.5% depending on the location. This means that the numbers above will look a bit better when you open the building, because presumably you have stayed on budget but your potential revenue has grown.

However, you might recall that Toronto very recently experienced rent escalation higher than 10% per year:

The Covid-19 pandemic might have created a unique set of conditions and inflation was running hot, but at the same time I think a bigger part of the story is simple supply and demand. We were bringing in lots of immigrants, and not building very much housing for them.

Next let’s look at what happens to your proforma if rent increases at just 4% per year for five years before project completion.

Not bad! What happens if rents grow at 6%?

Now, as I said before, I do not include scenarios like these in my proformas because A) it would be irresponsible of me as a steward of investor capital to rely on this kind of market movement for projecting returns, and B) I want my working model to show something closer to my downside scenario, not my upside.

At the same time, these upside scenarios are not low-probability events, for the reasons discussed above. Rental projects (in experienced hands) that start today may have a very bright future because of what’s happening in the world.

I’m not unique in noticing this opportunity, of course. I see many inexperienced developers attempting to move forward with rental projects where their downside is massive because of aggressive underwriting. I previously wrote about some of the major risks that new rental developers miss. These projects could lose millions for their investors.

Be careful out there.

If you are an investor with questions about rental investment, it would be great to connect with you. Reply to this email, message me on Substack, or visit my website.

If you are a condo developer who is considering a pivot to rental, but you are worried about execution risk — I love helping other professionals solve problems. Let’s talk.

That’s a wrap.

I write this newsletter because I like to connect with smart people who are doing interesting things. Feel free to reach out with questions or suggestions by replying to this email.

Thank you for reading, and have a great March.