In last month’s newsletter I wrote about work-outs, or the process by which a lender will sometimes renegotiate the terms of a loan in order to avoid or resolve a borrower’s default. Some of you reached out to ask for more information on this topic.

A deep dive into work-outs is difficult, because each situation is quite different. This month, I’ll write about a related topic: the personal risk that a developer takes in this business. This should give readers a better sense of how deals can go wrong, and what happens when they do. You’ll be able to infer some things about work-outs after reading this post.

There are a few key ideas I want to communicate, some of which might be surprising to people:

Many private developers, especially those just starting out, are required to risk their family’s well-being on every project. Some or all of their personal assets — their personal holding company, sometimes their house, their retirement accounts, their kids’ college savings — are at risk.

Having a small number of people assume this level of personal risk is what allows the whole housing system to function.

When things go wrong in real estate development, they can go really, really wrong.

Everyone is highly incentivized to avoid letting things go really, really wrong.

I will add a disclaimer here:

I have never gone bankrupt, nor have I had a project go into receivership. I’m not an attorney, and have no specialized experience with these kinds of legal processes. Everything I’m sharing in this post is based on my best understanding of how the system works, and on the documents that have been associated with my own projects in the past.

So I have a favor to ask: If you think I’ve gotten something wrong in today’s newsletter, please reach out so I can issue a future correction.

In recent months there has been a wave of news stories about very prominent developers showing signs of financial distress.

In Toronto, where I live, several notable projects have recently had trouble paying their trades and/or lenders. Some examples include Mirvish Village by Westbank, which is facing legal claims by some of its contractors, Canada’s tallest planned building, The One by Mizrahi, and several projects by Vandyk.

The Mizrahi project and some Vandyk projects have entered receivership, a legal process whereby a third-party professional is court-appointed to manage the affairs of a company or project. This can be a lawyer, an accountant, a consulting firm… it really depends on the expertise of the receiver and the particular challenges faced by the business. Because this process is administered by a public court, receivership proceedings put a lot of private information into the public domain. You can generally download these documents from your local court website. Here in Ontario, you can find them on the provincial court website (where, bizarrely, you need to pay for the privilege) or for free from the website of a court-appointed receiver. For example, Alvarez & Marshal has been appointed as receiver for The One, and you can read the various court documents here.

If you want a glimpse into the complexity of a typical infill residential project, I’d encourage you to read some of these documents. Today I will focus on one element, the personal guarantee.

What is a personal guarantee?

Let’s say there’s a rental project that a developer wants to build, and they think it will cost $100 million. This includes everything: land, fees & taxes, construction, consultants, etc.

A bank might be willing to loan 65% of the total costs for this project, and would require that the remaining 35% be funded by the developer as equity. Still, $65 million is a lot of money! The bank will understandably want a lot of assurances from the borrower about how and when the money will be spent. These assurances are recorded in a loan agreement signed between the bank and the borrower.

When a borrower negotiates a loan agreement, there’s a lot more to it than simply listing the loan principal, term, interest rate, monthly payments, and so on. The documents associated with a commercial real estate loan can run into the hundreds or even thousands of pages. These documents lay out the commitments of both lender and borrower in great detail, and are typically accompanied by many exhibits. A lot of ink is dedicated to the covenants of the borrower, i.e. the things that the borrower promises to do (and not do) as conditions for borrowing the money. Violating any of these covenants puts a borrower in default of the loan agreement, in exactly the same way that failing to make a monthly payment leads to default.

The bank will invariably make the borrower, and the borrower’s guarantor (more on this below), sign a handful of guarantees. For a large corporate developer, the business itself may have enough assets to serve as guarantor, and a personal guarantee isn’t required. For most private developers, the firm’s owners and/or investors are usually the guarantors (that’s the personal part). In either case, these documents are promises that the entity signing the guarantee will meet all of the bank’s conditions for the loan.

When I used to work in the US, it was very common for a bank to provide what is called non-recourse construction or permanent financing. This means that the bank would secure the loan with the project’s real estate as collateral, and if the borrower defaulted the bank could sell the land and hopefully recoup its loan principal and any accrued interest. If the sale of the real estate wasn’t enough to fully repay the loan, the lender could not come after the developer’s personal assets, except in extreme cases — fraud, gross negligence, or when losses result from very specific forms of default, like not purchasing insurance. The recourse available to the bank is limited to the value of the collateral, and any personal guarantee would be limited to these “bad boy” carve-outs.

I should add that US construction lenders do require a completion guarantee (and sometimes a cost overrun guarantee) which says that the guarantor personally promises that all of the borrower’s covenants in the loan agreement will be met, such as completing design, construction, and lease-up to a reasonable standard and within a certain budget. Notice this doesn’t mean the developer is personally liable if the market turns and the project doesn’t perform very well. If that happens, the developer will lose some of their equity and the bank bears some of the risk that a project won’t make its debt payments.

In Canada, lenders often require much more onerous guarantees with unlimited personal financial exposure for the developer. A typical US completion guarantee covers many of the same points regarding loan covenants/performance obligations, but generally limits personal exposure for business losses. (There’s a whole separate set of guarantees associated with equity investments, but let’s focus on debt guarantees today.)

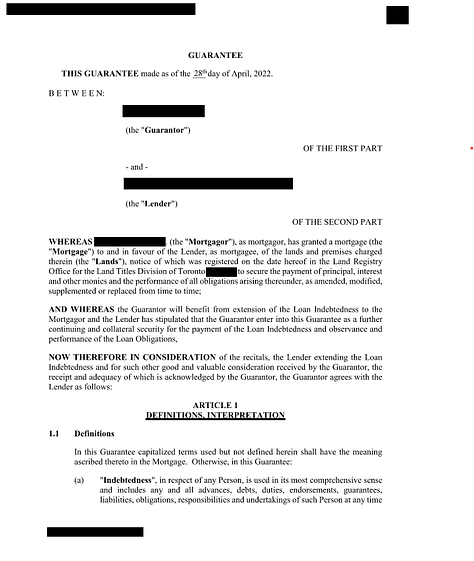

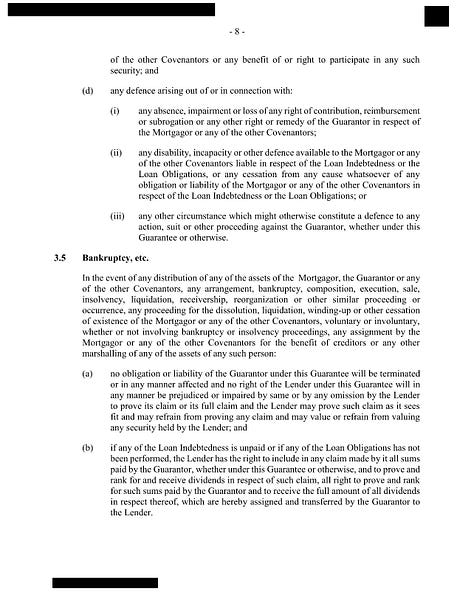

For a Canadian example, look at the gallery below where you will find the first several pages from a real personal guarantee. This document is associated with a number of mortgages for development projects in the Toronto region.

***Important Note*** These projects are currently in receivership, and the document below has been publicly posted by the court in Ontario. I have redacted it anyway, as a courtesy to all parties involved.

A few things to notice about this guarantee:

It is not between the developer’s corporation and the bank. It is between the developer (personally!) and the bank.

This means the developer personally guarantees all indebtedness, which extends beyond the loan balance, to include all liabilities, obligations, responsibilities, administrative expenses… basically anything that the borrower (the corporation) is responsible for.

The guarantor is personally responsible for making all payments related to the project, and indemnifies the bank against any and all losses/costs/liabilities.

The guarantee is irrevocable until the loan is indebtedness is entirely repaid — this means that even if the development business or project entity goes bankrupt, the guarantor is personally on the hook for full repayment.

The guarantor waives any right to receive communication from the bank, including notices or demands sent to the borrower.

It’s worth also saying that the loan principal associated with the particular guarantee shown above is more than $200 million.

When you sign a guarantee the bank will typically ask for personal financial statements prepared by your accountant, sometimes audited by a third party. That doesn’t necessarily mean that you need to have enough net worth sufficient to cover the loan balance, it’s more about signalling financial strength. They just want to see that you have enough assets to cover any likely losses if the deal blows up. In our example, a $65 million loan may only require $50 million in guarantees, or it may require the entire amount. What will make a lender comfortable varies by lender, and by project.

Another interesting practice in the industry is the sale of guarantees. For example, in a joint venture, it is usually the case that one of the partners has a bigger balance sheet or more liquidity, both of which strengthen that entity’s guarantee from the perspective of a lender. In such a case, one partner might provide the full guarantee, and charge the other partner a fee for this service (usually 1-3% of the guarantee value, paid once).

What Happens When a Project Fails?

So do banks actually go after the developer’s personal assets when a project fails?

Not usually.

Development is a risky and cyclical business. In every business cycle a portion of the players go bankrupt, whether corporately or personally. But once a project is underway, it’s really in nobody’s interest for the developer to go bankrupt.

This is important: Every large development project creates jobs for hundreds if not thousands of people. Investors and banks have a lot of capital at risk (and really it’s your capital — funded by deposits from ordinary people and investors alike). City governments will have spent a lot of time and resources on an approved project. Basically, there is a lot of social wealth tied up in one of these projects.

When it goes wrong, everyone who is connected to the project suffers. Consultants lose revenue, trade schedules get screwed up and sometimes contractors don’t get paid, new jobs that the project would have generated may never materialize, and new tax revenue is delayed or sometimes foregone. Banks and investment firms lose investor capital or receive lower returns. It’s really important to prevent this kind of social loss from materializing, whenever possible.

That means that when a development project starts to wobble, the bank doesn’t immediately place it into receivership and squeeze the developer for her personal assets. That’s a good way to make the developer stop working on a project and focus on defending against litigation. Instead, lenders and equity investors will usually work closely with a developer to get the project back on track. This is usually a very painful process in itself, but it’s much less painful than legal proceedings. It might involve supplementing the project with additional project oversight or financial controls; it might involve increasing the project budget with additional debt and/or equity; it might involve a forced buyout among the investors. It will often involve adding additional or partial guarantees to cover any new obligations of the borrower and developer.

You might be wondering, “if the bank doesn’t plan to go after the developer, then why have such a one-sided guarantee in the first place?”

This is another really important thing to understand about this business.

We live in a world where not many people have skin in the game. There are very few things a typical person can do at their job which would put their home, their life savings, and the well-being of their children at risk. Real estate development exists on a different plane of reality.

Personal guarantees are filled with lots of boilerplate and legalese, but at their essence they say: “screw this up, and we have the right to destroy you.”

Development deals are so complex, there is so much capital required, there is so much risk, and there are so many ways a developer could mess it up… it kind of makes sense that the developer must essentially sign their life away. Remember, a single project has hundreds of people (who are not the developer) and millions of dollars (which don’t belong to the developer) at risk.

Investors, banks, and regulators could try to endlessly micromanage a developer, spending lots of resources on managers to manage the managers… or they can simply hang a sword of Damocles over the developer’s head. This simple trade is at the heart of business: If you shoulder the full risk, you might just reap the full reward.

It’s part of what keeps a developer focused, and running as fast as they can toward the end goal for each project.

A special shout-out to Jonah Brown at Oakbank Capital for providing comments on this article, and for helping me avoid embarrassing mistakes. The stakes are low when you’re writing for people on Substack, but they can be huge when you’re dealing with debt and guarantees in real life. If you’re looking for debt advisory services, I highly recommend reaching out to Jonah’s team.

In The News

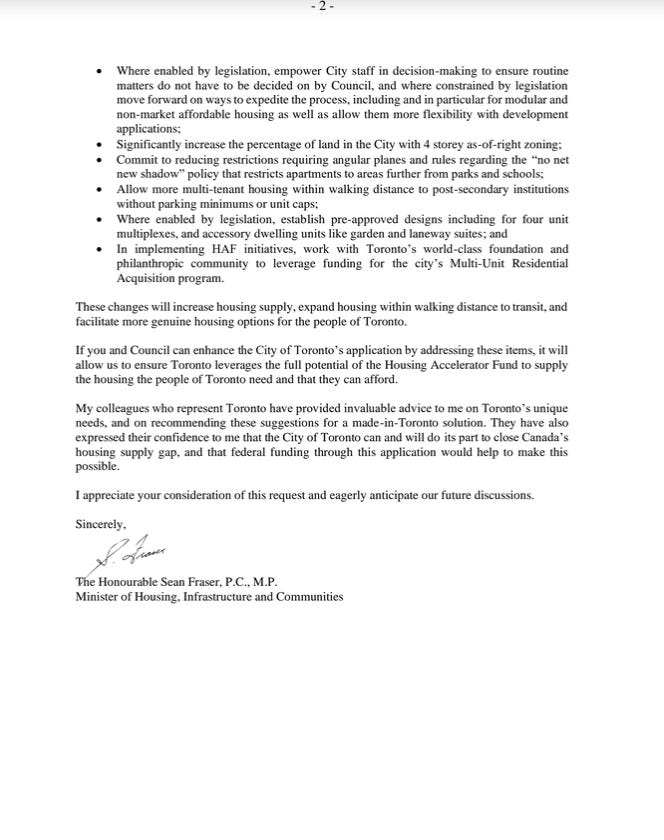

On November 22nd, Federal Housing Minister Sean Fraser sent a letter to Toronto’s mayor, Olivia Chow. It’s worth posting in full.

Cities across Canada can apply for money from the federal government’s Housing Accelerator Fund. Toronto had submitted an application, and held a follow up meeting with CMHC staff and the Minister to discuss the details. It sounds like Minister Fraser was not impressed with what city staff put forward, and he provided a list of eight items that he wanted to see in a revised application. These include taller building heights, more density, faster permits, and more as-of-right zoning across the city.

Mayor Chow, to her credit, has indicated that she is enthusiastic about making these changes, and she believes Council will support them. The devil is in the details, of course. Whether or not these changes lead to more approvals will depend on the implementing regulations. Toronto’s planning department has made a large number of reforms in past several years, such as loosening restrictions around laneway housing, garden suites, and multiplex buildings. Unfortunately, these changes have led to very few new housing units, mostly due to regulatory complexity and poor financial feasibility of what’s allowed to be built.

That’s a wrap.

I wish you all a great December. Happy Hanukkah to those who are celebrating this week, and a peaceful holiday season to all.

If you liked this post, please consider sharing with your friends.